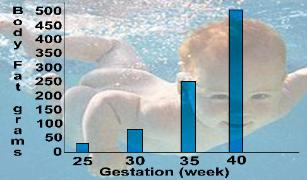

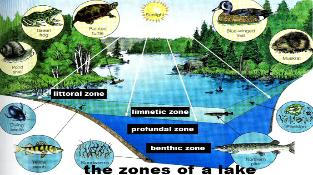

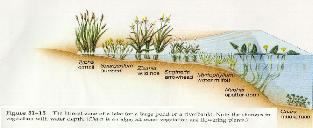

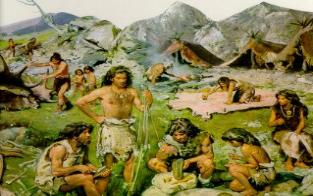

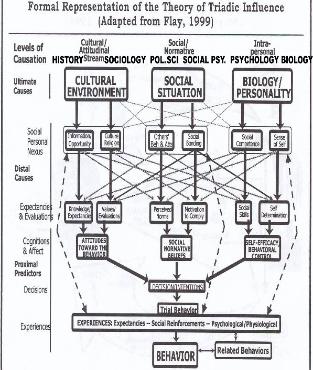

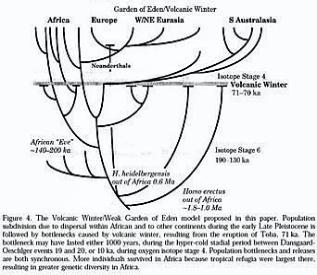

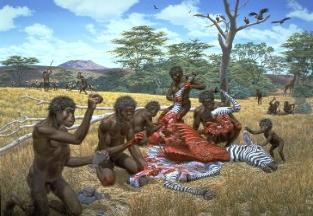

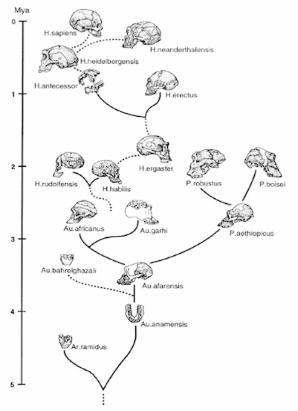

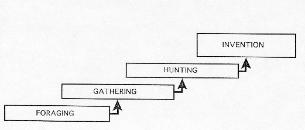

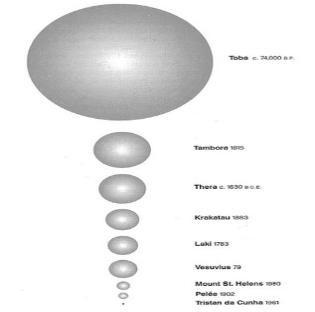

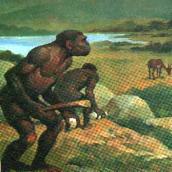

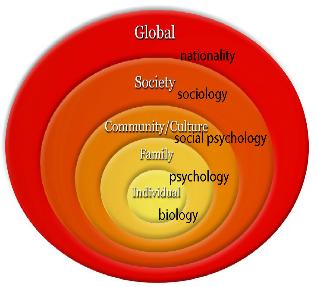

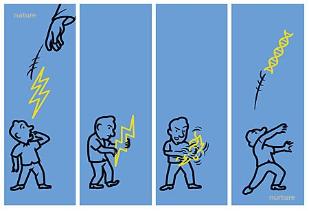

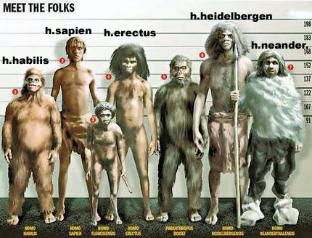

| “When any hypothesis… is advanced to explain a mental operation which is common to men and beasts, we must apply the same hypothesis to both.” - David Hume, Treatise of Human Nature, 1739 “Neuroscientists have given up looking for the seat of the soul, but they are still seeking what may be special about human brains, what it is that provides the basis for a level of self-awareness and complex emotions unlike those of other animals…. pathways and connections that are central in creating social emotions, a moral sense, even the feeling of free will? There are specialized neurons at work…. large, cigar-shaped cells called spindle cells.” - Sandra Blakeslee, “Humanity? Maybe Its in the Wiring”, 2003 ' People form the groups which we call nationalities, whether ethnic or civic in nature, to help them achieve objectives of overriding importance common to members of a group with which they identify. Almost invariably, the common objectives which create nationalities involve competition between one’s own group and one or more groups of outsiders. The competitive relationship may be only over comparative status (group ego) or it may involve conflicting material interests, perhaps extending to the very survival of one or more of the groups. Unfortunately national rivalries which often begin over status may sometimes evolve into a question of survival for one group or another. Groups perceiving common interests, if they do not already possess sovereign political authority, tend to pursue it avidly. They do so both because sovereignty enhances group status and because it greatly increases the power of the group to act in its own interests. ' The thesis of this chapter is that we humans share with several other animal species a hereditary behavioral predisposition to identify with one or another of two or more rival groups. The groups sharing such hereditary behavioural predisposition include not only our fellow primates (including monkeys, baboons, chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas), but also social carnivores (including lions, hyenas, wolves, and wild dogs). Social carnivores, although not among our primate relatives, did share our environment on the African savanna during much of our species’ formative era. Our primate precursors began to compete with the social carnivores for the means of subsistence on the savanna after diminishing rainfall had transformed much of the area from dense rain-forest into partially wooded grassland, the definition of savanna. ' Before surveying the common ground which our species shares with our fellow primates and social carnivores in terms of: 1) group formation, 2) dominance, 3) territoriality, and 4) cooperation and sharing, however, we must first examine some things about our species’ development that are unique. From Hominids to Homo Sapiens “Expanding a major organ like the brain would have required incremental, sustained and coordinated changes in gene expression. Random mutations would have almost zero likelihood of achieving such an outcome. The main environmental variable that could act in concert with and might promote a change in gene expression is diet.” - Stephen Cunnane, Canada Research Chair in Brain Metabolism and Aging, 2003 (20) ' In the late Miocene era, early hominids diverged from purely foraging primates and began the process of developing bipedalism and erect posture. As nutritionist Stephen Cunnane has noted, the earliest hominid fossils indicate that hominids "became bipedal long before they started using tools or ' before the brain had started to increase very much in size... one important deduction that follows (walking ' preceding tool use preceding a significant increase in brain size) is that evolution of bipedalism could not have ' depended on larger brain size to coordinate movement and balance… Why this was advantageous (or, in fact, ' acceptable) to the rest of the body?’” (Cunnane, 2005, 11). ' Traditional theories of hominid evolution have emphasized knuckle-walking and the gradual development of proto-tools from a sitting position,within the context of a decreasingly arboreal environment. As David Gordonton explains: “It is at least a possibility that the last common ancestor we shared with chimps spent a lot of time up trees, but walked bipedally. Our lineage would then have taken to spending increasing amounts of time on the ground and refined its bipedal mode of locomotion, while chimps- and gorillas… took to knuckle-walking” (Gordonton, 2006, 27). This presumes, however, the dry-land based environment and diet preferred by all (or nearly all) primate species today. A primary problem with this, as an increasing number of nutritionists have noted, is that land based diets are generally inferior to littoral and estuarine based diets in terms of naturally occurring essential fatty acids that the brain requires in order to grow. ' C. Leigh Broadhurst and colleagues found that the nutritional resources present in littoral foods could have provided an early homo species or group with a critical brain-power advantage over rivals, long prior to its eventual development of efficient bipedalism and hunting skills: The polyunsaturated fatty acid… composition of the mammalian central nervous system is almost wholly composed of two long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and arachidonic acid (AA). PUFA are dietarily essential, thus normal infant/neonatal brain, intellectual growth and development cannot be accomplished if they are deficient during pregnancy and lactation…. Littoral marine and lacustrine food chains provide consistently greater amounts of pre-formed LC-PUFA than the terrestrial food chain. Dietary levels of DHA are 2.5-100 fold higher for equivalent weights of marine fish or shellfish vs. lean or fat terrestrial meats. Mammalian brain tissue and bird egg yolks, especially from marine birds, are the richest terrestrial sources of LC-PUFA. However, land animal adipose fats have been linked to vascular disease and mental ill-health…. Exploitation of river, estuarine, stranded and spawning fish, shellfish and sea bird nestlings and eggs by Homo could have provided essential dietary LC-PUFA… without requiring organized hunting/fishing, or sophisticated social behavior. It is…predictable from the present evidence that exploitation of this food resource would have provided the advantage in multi-generational brain development. Restriction to land based foods as postulated by the savannah and other hypotheses would have led to degeneration of the brain and vascular system as happened without exception in all other land based apes and mammals as they evolved larger bodies” (Broadhurst, et al., 2002, 653). ' Cunnane and Crawford, noting the importance of such findings, point out also that “virtually all ages could then feed themselves, thereby allowing those that were so motivated to try their skills at tool making, hunting, trapping, fishing or scavenging carcasses” (Cunnane & Crawford, 2003, 21). Others have noted that our closest related species today, the relatively recently discovered bonobos (pan paniscus)- have been observed to use bipedalism less than 2 percent of the time they spend on land, but while in water spend the overwhelming proportion of their time wading (Kuliukas, 2002, 267). ' It is important to bear in mind that “among terrestrial mammals, the capacity to deposit fat on the fetus during pregnancy is apparently almost a uniquely human feature. Guinea pigs are born with some fat but are much more mature at birth than humans” (Widdowson, 1974, 19, 22). Indeed, at normal term, a newborn baby’s brain “consumes approximately 74% of the body’s energy intake.” In light of such facts, it should come as no surprise that the “past decade has seen a steady increase in reports linking early and later hominid evolution to lakes and seashores (Crawford & Marsh, 1989; Verhaegen, 1991; Cunnane, et al., 1993; Ellis, 1993; Stewart, 1994; Morgan, 1994; Parkington, 1999; Broadhurst, et al., 1998; Crawford, et al., 1999; Walter, et al., 2000; Tobias, 2002; Broadhurst, et al., 2002). Hominid exploitation of the rich and mostly sessile shore-based foods would, as skills improved, have been gradually supplemented by fishing, hunting and experimenting with cooking less nutritious roots, tubers, etc” (Cunnane & Crawford, 24). ' We should be mindful as well, as anthropologists Robert Sussman and Donna Hart assert, that predation was extensive throughout hominid evolution and was also a driving force for anatomical and behavioral evolution. In Man the Hunted (2005), they focus on the earliest genus of hominids to live primarily on the savannah, Australopithecus (approx. 4.5-2.5 mya). They show that A. afarensis, the longest surviving australopithecine (approx. 4-3 mya), did not have tools, “didn't have big teeth and wasn't very tall. He was using his brain, his agility and his social skills to get away from…predators…. Approximately 6 to 10 percent of… [A. afarensi] were preyed upon"- the same predation rate as for savannah antelope and certain ground-living monkey today (Shoenherr, 2005). Afarensi, who had a brain about the size of a chimpanzee’s, were “not dentally prepared” to eat meat, and formed large social groups for defence and protection, not for hunting (Shoenherr, 2005). ' In any event, be it by littoral or land based diet, there is general consensus that by around 2.5 mya the homo genus was regularly carving stone tools and had diverged from the australopithecine branch of hominids in the Rift Valley of east Africa. Concurrent developments included intensified ice age cycles in the northern hemisphere, the emergence of widespread grasslands and greater variability of climate, large-scale shifts in fauna, dramatic dietary changes to suit a variety of habitats, and further adaptations to upright posture and bipedalism (Bobe & Behensmeyer, 2004; Teaford & Ungar, 2000; Cunnane, 2005; Stiner, 2002). By about 2 mya, H. ruddolfensis (h. habilis) appears to have evolved the capacity for long-distance running, which is impossible in all other primates and mammals, with the exception of dogs, horses, and hyenas (Wilford, 2004). This new trait was ”probably decisive in the pursuit of high-protein food for development of large brains” (Wilford, 2004). The homo genus was now equipped to start moving beyond scavenging and gathering. ' Our ancestors could now directly compete with carnivores, even the social variety, for subsistence on the African savanna. Anthropologist P. Jeffrey Brantingham took note that this “hominid invasion of the predatory guild at least 2my ago would have brought them into contact with a range of new selective pressures” including conflicts with a range of large-bodied predators (Brantingham, 1998, 327). Allow him to introduce the concept of hominid-social carnivore coevolution on the savannah (327- 328): ' Throughout the course of hominid evolution, there appears to have been a consistent overlap both in the use of space and in the foraging strategies employed by hominids and large-bodied predators (Clutton-Brock 1996; Stiner 1991a,b, 1994). The persistence of hominid-carnivore associations through space and time ' raises the possibility that coevolutionary pressures have dramatically affected the course of both hominid ' and carnivore evolution…. The combined evidence implicates coevolutionary selective pressures as a major ' force in the evolution of the hominids (e.g. Shipman & Walker 1989; Walker 1984). Indeed, hominid-carnivore ' coevolution may have been integral to the evolution of a variety of unique human traits such as lithic ' technology (Blumenschine 1987), large brains (Aiello & Wheeler 1995), and complex social and foraging ' group organization [9 references]…. First, extensive habitual food transport is a key behavior distinguishing ' large-bodied predators from nonhuman primates (Potts 1991; Rose & Marshall 1996; Stinger 1994). Second, ' food transport is thought to be a primary behavioral mechanism for reducing levels of interspecific competition ' (Begon et al. 1990; Krebs & Davies 1993; Potts 1991; Stiner 1994; Vander Wall, 1990). ' The idea that hominids and social carnivores evolved certain affinities from their millions of years spent together on the savannah was put forth by zoologist Hans Kruuk (Kruuk, 2002) and others. According to Claudio Sillero-Zubiri “our attitudes to carnivores can be traced to the dominant presence of carnivores during early human evolution and that we evolved enduring their presence…. We have lived and competed with them, defended ourselves against them, used them, domesticated some of them, finally coming to love and admire them” (Sillero-Zubiri, 2003, 630). The main idea of coevolution is that “competition tends to escalate in high-density [prey] situations and where food is highly concentrated” (e.g., Kruuk, 1972; Sinclair & Norton-Griffiths, 1979; Stanford, 2001; as cited by Stiner, 2002, 39). ' Although new findings and technologies can change the approximate dates to (usually) minor degrees, there appears to be general consensus that h. erectus (1.8-0.3 mya) and the geologic Pleistocene era (concurrent with the anthropology’s Paleolithic era) each started around 1.8 mya. Erectus marked a departure from earlier hominids in that, as the name implies, its posture and bipedalism appear to have been completely developed from the start, and its brain capacity could be nearly twice that of h. habilis (2.5-1.7 mya). However, an erectus 'Mojokerto child' (from 1.8 mya) indicates an “endocranial capacity at 72-84% of an average adult H. erectus. This pattern of relative brain growth resembles that of living apes… [indicating that] major differences in the development of cognitive capabilities existed between H. erectus and anatomically modern humans” (Coqueugniot, et al, 2004). These first truly adventuresome hominids occupied a higher position in the predatory guild, and- as much of East Africa was in the process of becoming hot and dry- followed migrating ugulate herds into Asia and Europe, “accompanied by a suite of large mammals that included the primitive hyena… and the saber-toothed cat…” (Arribas & Palmqvist, 1999; Martinez-Navarro & Palmqvist, 1995; as cited by Stiner, 7). Hunting became even more important in these new climes due to winter months. Anthropologist Mary Stiner adds that crucial ecological differences “can be seen from which populations withdrew from northern fringes of their range as climate deteriorated and which did not… hominids and spotted hyenas stayed put. The extinction of several archaic carnivores (Eisenberg, 1981; Turner, 1986) apparently left room for new niches in Eurasia, soon filled by spotted hyenas (Crocuta), hominids, and other versatile opportunists” (Stiner, 2002, 7). ' The development of speech and the use of fire no doubt contributed greatly to h. erecti’s expansion beyond the traditional confines of the Rift Valley. Fossil evidence “points to modern adaptations for speech appearing between 1.5 million and 500,000 years ago” (de Boer, 2005, 281). Interestingly, most datings for early usages and cultivation of fire are within this same broad range (Flinn, et al, 2005, 22). Mark Flinn (et al) also points out that a “modern pattern of dental development was present by 800 kya (Bermudez de Castro et al., 1999),” although “delayed maturation and an adolescent growth spurt may have evolved later…” (Flinn, et al, 27). By the early mid Pleistocene (c.100 kya) however, “dimorphism was similar to that found in modern humans…. The body mass increase accompanying the origin of H. erectus suggests that female body size increased from the australopithecine condition more than did male” (24-25) (see Fig.2:2). Other recent studies, however, claim that this near-modern dimorphism rate was evident in A. afarensis (approx. 4-3mya), indicating that the roots of monogamous-type social behaviours in hominids go rather far back (Larsen, 2003). ' H. erecti and other hominid sub-species were clearly developing hunting and social skills at a faster rate than had any of their predecessors. Prehistorian Steven Mithen claims that there was a resultant “change in human-animal interactions with expansion of hominid brain size and the significance of animal meat in diets… [concurrent with a] dramatic enlargement in brain size between 600,000 and 250,000 years ago and direct evidence of big game hunting” (Mithen, 1999, 195). Perhaps the tables were turning in nature’s contest for interspecies dominance on the savannah and elsewhere. Stiner would seem to agree, noting widespread use of fire and “a burgeoning emphasis on some generalized form of ungulate hunting” around half a million years ago if not earlier (Stiner, 36). It would appear that in evolutionary terms, humanity’s first and most formative campaign for armed dominance was a sustained ‘war on animals’ starting with the systemic cultivation of fire probably more than half a million years ago and ending in victory and ecological/environmental superiority sometime around 250,000 years ago. This date marks the "earliest appearance of prime-aged-biased ungulate hunting, an ecological development that separates the hominid niche from those of other large predators. Middle Paleolithic technology also appeared around this time, likely including greater hide-working and tanning. A narrower range of prey were exploited than before” (40). This broader era, circa 300-100 kya, is also a traditional date for the displacement of h. erectus (and h. heidelbergensis) with early h. sapiens. ' Whatever one’s estimate of the date at which man-the-hunter achieved interspecies paramountcy, it is clear that as this “ecological dominance increased, the traits that began to strongly ' covary with individual differences in survival and reproductive outcomes were those that allowed hominins to ' socially ‘outmaneuver’ other hominins. These traits would include sophisticated social competencies, such as language, self-awareness… and reciprocity-based social coalitions. An extended period of childhood with ' intensive parenting would contribute to the acquisition of social skills and the development of personal social ' networks. The use of mental simulations and abstract mental models are necessary for the complex analysis ' of social relationships and networks” (Gallagher & Fish, 2003; Geary, 2005; as cited in Flinn, et al, 36). ' After our species attained dominance over all others there ensued what must have been a relatively tranquil period. This was the interval which occurred between the victory over animals (c.250 kya) and before population pressures would bring about warfare and organized conflict among humans (from c. 15 kya) (see Fig. 2.1, below). This is the approximate point at which analysis of nationalities should begin- when human populations first grew dense enough to necessitate an ‘imaginary community’ or tribe beyond the number of individual faces or names that could be remembered. The larger picture, however- of how we became bipedal, how we developed a brain so much superior to the brains of competitors, how we mastered fire and developed language- demands explanation as requisite background to the story of the persistence of tribal and nationalist rivalries within our species over the past 15,000 years. ' The overall process of human evolution does not seem to have slowed during this shift from predominantly interspecies conflict to factors affecting primarily competition among groups of humans. On the contrary, the “intensified processing solutions lent greater stability to humans’ lives and thereby may have enhanced child survivorship… [as] fire [in particular]… as a source of heat must have lessened the total energy demands on the human metabolism” (Stiner, 35). With a recurrent cycle of greater hunting success and fire leading to less energy requirements and more free time for child development, innovative tools and technology ensued. It is perhaps from such cycles that physically weaker and more neurotic children could survive to adulthood, aiding in the group selection of certain hunter-gatherer groups with more creativity in terms of dealing with their environment. As Stiner notes, there is “considerable room for changes in the amount of time and associated risks that people incur while hunting large prey” (36). ' H. sapiens, scholars have too often overlooked, have always been a highly social species and subject to the evolutionary pressures of group selection. We contrast this in respect to, for example, sharks, which are solitary and merely individually selected. Group selection [see Lexicon] tends to favor more diverse characteristics (and in humans mentally diverse characteristics), whereas individual selection favors a more narrow model of uniformity. According to anthropologist Joseph Henrich and others, the “rates of cultural evolution under group selection (decades, centuries and millennia) have about the right time scale to explain human history (Diamond, 1997), whereas genetic explanations are too slow…” (Henrich, 2004, 31). Intraspecies conflict, however, appears not to have been a salient factor in the earlier stages of prehistory, as hominid populations were "very small and highly dispersed prior to the Middle Paleolithic” (38) [c.100-35 kya]. Figure 2.1: Hominid and Human Social Evolutionary Eras Time Era Trophic/Economy Cooperation/Conflict U-Curve1 13 kbc- ? Intraspecific plant proteins, herding; great demogr. increases; initial sharp rise; ' Conflict mixed; processed high risk poverty/hunger reversed 20thc ' (Warring States) 250-13 kbc Garden of prime-age biased high cooperation and low point; ' Eden large game; gathering radiation of early technology egalitarian ethos ' 650-250 kbc Interspecific gathering; some ungulate increased hunter lowering; some ' Conflict hunting & fire/roasting cooperation extensive teamwork ' (War on Animals) 2.5-0.6 mya Coexistence foraging/scavenging; cooperative stealing; starts to lower ' desultory hunting some tools 7-2.5 mya Prey foraging/scrounging high risk from carnivores high; individual ' The era from about 130-74 kya was a generally warmer period, the most recent interglacial era prior to today’s Holocene interglacial (from c.12 kya- present). Early h. sapiens had already developed some long-distance trade, proto-jewellery, and sophisticated freshwater fishing tackle. All this changed, however, around 72,000 BCE with the eruption of Mount Toba in Indonesia. ' The explosion of Mt. Toba, the largest volcanic eruption of the past two million years, initiated or at least coincided with the most recent glacial expansion era. It shrouded the planet in some degree of volcanic winter for at least a few years (Gathorne-Hardy & Harcourt-Smith, 2003). African Anthropologist Stanley Ambrose and others, however, see a more pronounced effect. They claim that the Pleistocene super-volcano dropped temperatures more than 6°C in Greenland, the first of “three climatic events spanning 11,500 years, or 550 generations… [first, the] six-year volcanic winter at 71 ka. The 1000-year instant ice age it apparently initiated, and the early last glacial maximum… from 68 to 59.5 ka… [comprising over] 9% of the time since the origin of modern humans (Rogers and Jorde, 1995)” (Ambrose, 2003). Moreover, Ambrose asserts that “virtually all studies of the genetic structure of living human populations that have analyzed the history of past population size have identified a significant late Pleistocene human population bottleneck… [and an] expansion from a very small population size in Africa, continues to be consistently identified (Forster et al., 2001, Gagneux et al., 1999, Harpending and Rogers, 2000, Jin et al., 1999, Jorde et al., 1998, Marth et al., 2002, Pritchard et al., 1999, Qamar et al., 1999, Quintana-Murci et al., 1999, Rogers, 2001, Takahata et al., 2001, Underhill et al., 2000, Thomson et al., 2000 and Watkins et al., 2001). Two major bottlenecks/expansions occurred soon after the African bottleneck (Jin, et al., 1999, Qamar, et al., 1999, Quintana-Murci, et .al., 1999, Underhill, et al., 2000 and Zeitkiewicz, et al.,1998). These are likely to be founder effects of small populations leaving Africa (Ambrose, 2003 and Lahr and Foley, 1998). It is clear that the African bottleneck occurred prior to, but close in time to these colonization bottlenecks (Ambrose, 2003). ' Ambrose is not far from the consensus in stating that during the “last interglacial (128-74 kya), substantial steps were taken toward modern patterns of symbolic behavior, and sophisticated technologies and adaptive strategies were in their initial stages of development… [a trend] apparently accelerating during the latter half of the last interglacial” (See Watts, 1999; and Henshilwood et al., 2002; as cited in Ambrose, 2003). ' Interestingly, however, “social strategies of macro-regional integration and cooperation, which are adaptive in unpredictable environments, seem to have been comparatively poorly developed in the last interglacial, and territorial defense rather than intergroup cooperation was apparently the norm” (Ambrose & Lorenz, 1990; as cited in Ambrose, 2003). Ambrose notes, however, a post-Toba “troop- to-tribe” transition, as “weak macro-regional integration of local foraging groups during the early middle stone age (and early stone age) implies socio-territorial organization more like that of primate troops than human tribes. Risky environments of the early last glacial era may have promoted integration of local foraging troops into tribal social networks” (Ambrose, 2004). So basically, post- Toba harsher conditions sustained over a lengthy period killed off much of the early human populations in northern latitudes (where signs of inhabitation by hominin have typically been sporadic); while perhaps no more than 5,000-10,000 survivors in Africa (and perhaps also lesser numbers in India) were “selected strongly for an unprecedented degree of social cooperation and information exchange between individuals and groups over large areas… at very low population densities… evinced by the remarkable scarcity of archaeological sites of this period throughout Africa” (Ambrose, 2003). After several thousand years of such conditions, homo sapiens sapiens (sometimes identified with the term Cro-Magnon man and erroneously associated only with Europe) began to migrate out of Africa and into southern Eurasia, Australia, and eastern Europe. Thus, we are all “the descendants of the few small groups of tropical Africans who united in the face of adversity” (Ambrose, 2003). ' One might add that survivor rates in Africa (or anywhere else) would likely have been higher along sea coasts and other resilient, milder environments. Here, over a number of generations, the superior nutrients of a littoral-based diet could have enabled further brain expansion and mental evolution- particularly given original founder effects. As mentioned above, brain optimization and growth in particular require certain nutrients. ' Even evolutionary specialists who do not mention Toba theory tend to agree that “mtDNA lineage- analysis patterns point to a major demographic expansion centered broadly within the time range from 80,000 to 60,000 B.P., probably deriving from a small geographical region of Africa” (Mellars, 2006a, 9381). Archaeologist Paul Mellars contends, moreover, that “recent archaeological discoveries in southern and eastern Africa suggest that, at approximately the same time, there was a major increase in the complexity of the technological, economic, social, and cognitive behavior of certain African groups, which could have led to a major demographic expansion of these groups” (9381). ' By all accounts, the emergence of Cro-Magnons would dramatically change mankind’s relationship with the environment. As far back as 60 kya the earliest immigrants to Australia were painting (Skomal, 2006), and by around 50 kya a creative explosion or great leap forward was sweeping across Eurasia. Mellars has concluded that this much-debated dispersal of modern populations from Africa sometime between 60-40 kya was “according to the latest archaeological and genetic evidence… a single successful dispersal event, which took genetically and culturally modern populations fairly rapidly across southern and southeastern Asia into Australasia, and with only a secondary and later dispersal into Europe” (Mellars, 2006b, 796). ' In the words of Mary Stiner, “initial Upper Paleolithic cultures appeared between 50 and 45 kya and spread across Eurasia like wild fire… replacing all Mousterian [flake tool] cultures by 28-30 KYA… [as] material culture accelerated on multiple fronts… indeed expanded to include visual communication” (Stiner, 40). Moreover, as material success increased survivorship and longevity, by about 30 kya the number of people living “long enough to become grandparents dramatically increased. There were now two adults over 30 for every adult under 30. With more adults available to provide child care, humans began to develop more complex social systems” (Skomal, 2006). ' According to philosophers John Sarnecki and Matthew Sponheimer, prior to 50 kya “anatomically modern humans and Neanderthals produced more or less identical toolkits” (Sarnecki & Sponheimer, 2002, 182). Yet soon thereafter, “not only are new toolkits developed, they are often replaced ' wholesale. We… begin to see evidence of rituals and the blossoming of artistic traditions…. ' What’s more, new developments began to follow in tens of thousands of years, rather than in hundreds of ' thousands and millions…. It is at this point in our development, [prehistorian Stephen] Mithen claims, that the ' modern mind takes shape… [when] the creative imagination was born, resulting in analogical thinking, art, ' religion, and increasingly complex inventions…. In contrast, Neanderthals and their antecedents were ' incapable of analogical thinking” (Sarnecki & Sponheimer, 2002, 181, 174-75). Yet the neurological changes presumably necessary for such radical changes in culture are “not visible osteologically” around 50 kya (Sarnecki & Sponheimer,182); and it has long been known that Neanderthals often had larger brains than their Cro-Magnon neighbors. It appears then that the mental developments associated with the advent of Cro-Magnons were primarily organizational. This relates to complex language development, the resultant ability to articulate abstractions, and other abilities to make mental connections between non-ostensibly related objects and thoughts. Recently discovered 'spindle cells' in the anterior cingulate cortex have been shown to be pivotal in our ability to manage stimuli from different regions of the brain in a socially appropriate manner- and can thus (also) be thought of as a development towards more sophisticated brain organization and fluid thought processes. “{I}f anything marks us as distinctive from other animals it is the power to discriminate amongst…kinds of alternatives” (Sarnecki & Sponheimer, 181). Before long there would be other types of discrimination as well. Stiner has found indications of sustained demographic increase in Europe from after 45 kya. Due to such gradually increasing intraspecific pressures, the ensuing Upper Paleolithic era (c.35-10 kya) “is the first major period in which visual signals of ‘ethnicity’ or individual identity are apparent (sensu Wobst, 1977)… a marked regionalization of artifact styles… [although] the demographic conditions that make large, open-ended networks numerically possible seem to have evolved quite late in the Paleolithic” (Stiner, 39). It is significant that as hunter-gatherer populations reached a certain level, they experienced less inter- migration per capita, as it was no longer necessary in order to avoid inbreeding. Despite many thousands of years of increasing demographic pressures, however, it is not until around 14 kya that we have the first clear evidence for mass intraspecies conflict- the Cemetery 117 mass grave of child war victims in northern Sudan (Guilaine & Zammit, 2005). Anthropologist Lawrence Keeley has found that “hominids were hunters of large game hundreds of thousands, possibly 2 million, years before any unambiguous evidence of homicide, let alone group homicides or warfare” (Keeley, 2006, 262). Based upon either 500,000, or 2 million, years of some kind of group hunting, this estimate from Keeley represents 97-99 percent of human evolution. After the last glacial maximum of around 22-20 kya and “the evolution of ‘complex’ hunter-gatherers in many areas” (Stiner, 39), small, isolated groups of people first began to cross over from Siberia into the Americas. By the time that rapid deglaciation set in about 14.5 kya, populations in the Western Hemisphere had substantially increased; while back east people were expanding far into northern Europe and Siberia. These efficient hunters often left a trail of extinctions in their wake, starting from 13 kya in northern Eurasia, and 11 kya in North America (in addition to 50 kya in Australia). Paleobiologist Anthony Barnosky (et al) has found that of more than 150 genera of megafauna (weighing more than 44 kg.) living on land 50 kya, at least 97 were extinct by 10 kya (Barnosky, 2004, 70). This includes all herbivores over 1,000 kg., and 75 percent of herbivores from 100-1,000 kg. While the overhunting theory seems apt for Australia (with its particular marsupial fauna) and perhaps North America2, where animals had not enough time to evolve defenses to the new human threat, Barnosky cautions against any generalist model of “blitzkrieg sensu stricto” extinctions: “The recent information now points toward humans precipitating the [late Pleistocene global] extinction, but also to an instrumental role for late Pleistocene climate change in controlling its timing, geographic details, and perhaps magnitude” (74). With the Neolithic (agricultural) revolution, all this began to change even more quickly. But before visiting that topic (primarily in the next chapter), let us preview some key aspects of our species’ divergence from other primates. What were some of the major ways in which we came to differ from our fellow primates? One way is that our teeth became adapted to eating water-storing roots which are abundant in the savanna, but not in the rain forest. Still more important is that we came to rely more on meat-eating than do other primates. Other primates are more nearly frugivorous and herbivorous. They subsist chiefly on fruit, leaves, and other plant material. It is true that chimpanzees in particular eat insects as well and the flesh of other animals, even their own kind on occasion. Chimpanzees eat meat with such obvious enjoyment that one is tempted to suggest that our ancestors may have 'left the trees' and taken up hunting in order to get away from the monotony of a vegetarian diet. Chimpanzees, however, are not the best of hunters and thus usually do without meat (Goodall, 1986; cf Mitani & Watts, 2001). On the other hand, at least some hominids (h. erectus, h. heidelbergensis) had become a very good hunters by the early-to-mid Pleistocene era (1.3-0.3 mya). Meat, while affording less caloric intake than plant foods in the diet of our ancestors, came to comprise the most highly valued portion of their menus. This remains true for our species today in most homes and restaurants, despite the fact that both our digestive systems and most of our bodies (with perhaps the exception of the brain) tend to do better if we consume less meat and more fruits and vegetables. The high energy value of meat compared to vegetable matter also afforded our ancestors, as it does carnivores in general, vastly more leisure time than can be afforded by our more nearly frugivorous and herbivorous relatives. Nonhuman primates, like most herbivores, must browse during many of their waking hours in order to get enough caloric intake to stay alive. Over the course of several million years, fundamental physical and behavioural adaptations occurred. Let us summarize them. Erect posture and bipedal locomotion freed the hands for carrying and for using tools or weapons while in motion. Carrying was crucial not only for food, tools, or weapons, but also for babies, which in our species are much more fully dependent and for a longer period than other mammals. Bipedalism also reduced the energy requirement for walking, thus enabling hominids to widen their range, as well as affording a higher plane of binocular vision. The ability to cool ourselves by perspiration enhanced stamina for extended exertions like long distance running. A more fully opposable thumb made human hands more useful in grasping and throwing. Females developed a wider pelvis, permitting the birth of babies with larger brains. All-season sexual responsiveness replaced seasonal sexuality, enhancing the pair bond which certainly contrasts with the promiscuity of our closest primate relatives. Human infancy and childhood lengthened, permitting greater brain growth and mental development after birth (Weiss & Mann, 1990; Fagan, 2001; Goodall, 1986; Kingdon, 2003). Still another major change produced the capacity for speech, which eventually led to the development of languages and complex abraction (Chomsky, 1965; Deacon, 1997; Pinker, 2002). Major behavioral changes supplemented the biological differentiation of human from nonhuman primates. Pair-bonding and a father role became significant. Division of labor arose as females tended to stay with their children and gather plant foods, the major portion of the diet, while males took increasingly long hunting trips. Sharing of food came to be characteristic, replacing the individual self- reliance in feeding which is typical of nonhuman primates in the wild (Fagan, 2001, 35 ff). That all of these evolutionary adaptations occurred after our ancestors 'left the trees' (or perhaps shores and swamps) for the rigors of savanna life suggests that behavioral adaptations which helped social carnivores to survive by hunting may have had similar influences on hominid survival. Accordingly, we shall now examine group formation and membership, dominance, territoriality, and cooperation & sharing among social carnivore species; as well as among nonhuman primates, hunter- gatherers, and finally contemporary people. A Closer Look at Evolutionary Behavioral Predispositions “The strongest evoker of aggressive response in animals is the sight of a stranger, especially a territorial intruder” - Edward O. Wilson, Sociobiology, 1975 In terms of research on nationality and nationalism, our evolutionary view contrasts with those of virtually all others who have written on the subject. It clashes in particular with the view of “Modernists” such as Kedourie (1960) and Hobsbawm (1990). They see nationalities as the product of an ideology of “nationalism” developed in Europe in the era touched off by the French Revolution and diffused from Europe to the rest of the world. Our deeper perspective, however, also clashes with the “primordialist” concept of Shils (1957) and Geertz (1963), later modified by Anthony D. Smith (1986), which sees nationalities as always the product of an ethnic identity (see chapter 1). The remainder of this chapter will take a closer look at the behavioral predispositions which we believe underlie the creation of nationalities. We shall do so within these four contexts: A) group formation and membership, B) dominance relationships, C) territoriality, and D) cooperation & sharing. In these four contexts, we will look successively at the behavior of: 1) nonhuman primates 2) social carnivores 3) prehistoric humans 4) modern humans. Our emphasis upon hereditary predispositions in human behavior might seem to link this study to those of the early “primordialists” who argued that an individual’s nationality is fixed immutably by birth into a particular ancestral or cultural group. On the contrary, we will show that, like our primate relatives who have inherited a group identity, we may in fact abandon our native group. We may do so either as individuals or in groups. We may abandon one group for another, create an entirely new nationality of either the kin-ethnic or the territorial-civic variety, or abandon any form of national identity for a preoccupying individual dependence upon a charismatic leader or institution. The pages which follow will consider the deeper evolutionary background of how people make these choices. The decision to look within the field of animal behavior for possible insights on the formation of nationalities derives from the assumption that human behavior is subject to influences originating in the genetic makeup of our species. That assumption can be controversial. Early in the previous century psychologists identified a wide range of "instincts" alleged to affect, if not determine, human behavior (McDougall, 1920). Before mid-century, those ideas had been repudiated and indeed largely replaced by the similarly extreme views of behavioral psychologists (Watson, 1925; Skinner, 1974). Their view was that human behavior is learned; that there is no hereditary influence upon it. Exploding knowledge about genes and their influence on humans as well as other animals has in recent years invalidated the presumption underlying this long-running argument over “nature versus nurture.” Biopsychologist Martha McClintock stated the emerging consensus succinctly when interviewed by the New York Times (February 5, 2003) on the 50th anniversary of the discovery of DNA. She observed: “There’s a constant back and forth between genes and the environment. It’s important to remember that genes came to be what they are solely because of their capacity to interact with the environment, and make the right products in response to the environment.” Thus we have been programmed primarily, it appears, to be adaptive- to adjust to changing environmental circumstances. Some have suggested indeed that frequent and extreme changes in climate during our species’ formative years may have helped our species to become adaptive and thus, unlike most species, to adjust to living on nearly all land areas of the planet (e.g. Calvin, 2002; Stanley, 1996; Boehm, 1999, 195). This high degree of adaptability built into our genetic makeup requires consideration of the assumption underlying both this chapter and the book as a whole. That assumption is that because national rivalries have been so threatening to the welfare, or perhaps even the survival, of our species and others, that we must do what we can to improve our understanding of them. Among the possibilities warranting investigation is that hereditary behavioral characteristics which we share with some other animals may affect significantly both the formation and the competitive relationships (maintenance) of nationalities. Until we can rule out that possibility with absolute certainty, we ought to consider very carefully the possibility that they do. Whether recognizing such evolutionary factors (presuming they exist) will help us learn to control them is of course another question. The extreme adaptability of our species, while perhaps raising doubt as to any genetic influence on human behavior as it relates to nationalities, suggests also that recognizing such hereditary influences might very well help us learn to control them. Findings relating to the operation of the human brain reinforce the idea that genetic influences which we share with some other animals may affect the development of national identities. Evolution, John Paul Scott observed (1989, 111), has not so much altered our brains as added to them. Accordingly, the nature and functions of the more primitive portion of the human brain, the amygdala, bear a strong resemblance to those of a wide range of other animals. Studies of the amygdala show that it responds more rapidly, and in some circumstances more forcefully, than does the more deliberative portion of the brain. The suggestion emerging from these findings is that some emotions, and even actions based upon them, can occur before the more deliberative portion of the brain has had time even to register what it is that is causing the reaction. Indeed Joseph LeDoux has asserted that “Emotional responses are, for the most part, generated unconsciously” and that “absence of awareness is the rule of mental life rather than the exception throughout the animal kingdom” (LeDoux, 1996, 17; 2002). As early as 1992 one authority expressed confidence that the amygdala "plays an influential role in a wide range of behaviours" (Amaral, 1992, 57). More recently Jorge L. Armony (2002) affirmed bluntly that “It is now generally accepted that the amygdala is a critical component of the neural system involved in learning about stimuli that signal threat.” “The neural system involved in learning about dangerous stimuli,” he added, “has evolved very early in the phylogenetic scale and has remained essentially unchanged throughout evolution.” It has the capacity, he continued, “to integrate this information and, if appropriate, retrieve it and elicit a host of species-specific responses” (319). Antonio Damasio (2003, 40) went farther. He affirmed that racial and social prejudice (might he have added national rivalries?) derive in part from the “automatic deployment of social emotions evolutionarily (sic) meant to detect difference in others because difference may signal risk or danger, and promote withdrawal or aggression.” He concluded these observations with the more hopeful suggestion that individuals of our species “can learn to disregard such reactions and persuade others to do the same.” Authorities have established also that fear is the reaction most closely associated with the amygdala (Aggleton, 1992, but see also Adolphs, 1999; Anderson & Phelps, 2000; Armony, 2002; Babinsky, 1993; Bear, 1991; Damasio, 2003; Davis & Whalen, 2001; Hines, 1992; Kapp, 1991; LeDoux, 1996, 2002; Leonard, 1985; Ohman, 2002; Rolls, 1990, 1992, 2000; Whalen, 2001; Winston, 2002). Thus we need to consider the possibility that behavioral patterns relating to feelings of national identity and rivalry, especially to fear of other groups, may occur without conscious consideration and may reflect influences from this primitive portion of the brain. We need to consider also that human behavior in this respect may be similar to the behavior of other animals whose amygdalas function very much as does ours, especially with reference to reactions such as fear. What we know of human evolution makes it appear appropriate to look in particular at two major categories of animals for evidence of hereditary influence relating to the formation and the competitive relationship of groups. The first of these is our fellow primates, especially those most closely related to us- chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas- but also our somewhat more distant relatives, baboons and other monkeys. Our genetic makeup is over 98% identical with that of bonobos, chimpanzees, and gorillas; somewhat less for other primates (Jeffreys, 1989; Waal, 1997). This fact creates a strong presumption that if there are hereditary behavioral patterns among them related to such matters as group formation and membership, dominance, territoriality, cooperation and sharing, then there may well be similar patterns in human behavior. At least, as noted above, we ought to consider that possibility quite carefully unless or until we can rule it out. The second category of animals to which we need to look for hints as to possible hereditary influence on our behavior is social carnivores, in particular lions, hyenas, wolves, and African wild dogs. Although social carnivores are obviously not as closely related to us as are our primate relatives, what we share with them in an evolutionary context is, first, a large portion of our mammalian genetic makeup. Second is a long period of adaptation to living in partially-wooded grassland (savanna) and some appreciable dependence upon hunting. Experts are increasingly disposed to find influences of the savanna environment (see coevolution, above) upon the evolution of both social carnivores and humans. Major genetic difference between humans and our closest primate relatives clearly came about after some of our arboreal ancestors 'left the trees', whose numbers were thinning due to reduced rainfall, and eventually began to compete with social carnivores on the savanna. Evolutionary adaptation to bipedalism, and to increased dependence upon root-eating, scavenging, an the rewards of hunting produced in time a hominid species quite different from even our closest primate relatives today. Group Formation and Membership What patterns are there relating to group formation and membership among nonhuman primates? Monkeys come in many varieties with remarkably different patterns of social behavior, but some cautious generalizations are in order. First monkey groups are invariably female-based. Maturing males leave their native groups. In seeking acceptance into a new group they usually encounter strong hostility, especially from males high in the dominance order. They respond usually with submissive rather than aggressive behavior, and almost invariably win eventual acceptance. They then give great loyalty to their new group, even when it is in conflict with their native group. The importance of the group is evident also in that captive individuals raised in isolation are almost always very deficient in social relationships. One monkey, observers of their behavior sometimes affirm, is no monkey (Henzi & Lucas, 1980; Cheney, 1981,1982, 1987; Cheney & Seyfarth, 1990; Bernstein, 1993; Takahata, 1994; Schuster, 1993; Estrada. 1977, 1978; Gust, 1995; Lyons, 1994; Watanabi, 2001; Seyfarth & Cheney, 2003). Baboons, like monkeys (scientifically they are monkeys), come in a number of varieties differentiated chiefly by whether they live in forests or in open area. Permanent members of the groups are female. Males leave their native group at sexual maturity and may, with nomadic intervals, change groups several times during their lives. They rarely stay in any group longer than five years, the approximate time required for their first female offspring to become sexually receptive. Some baboon groups consist of several harems, but in other multi-male groups each male tends to establish long term "friendships" with several females. Although these females may mate with others as well as with their friends, a male friend tends to be quite protective not only of his female associates, but also of her offspring. As males are roughly twice the size of females and sometimes prone to infanticide, this protection against other males is quite useful for a female and her young. In open country, males may defend their group staunchly against predators; in forest-dwelling groups they do not. When baboon groups split, it is often along lines of status, i.e. high-ranking individuals go with one group and those of lower rank with the other (Pusey & Packer, 1987; Walters & Seyfarth, 1987; Smith, 1992; Smuts, 1985; Strum, 1987; Kummer, 1967; 1995; Bercovitch, 1995). Gorilla groups come in three varieties. Some groups consist of a single silver-back male plus a number of females and their offspring. Other groups may include young (black-back) males and at times a second silver-back. Still other gorilla groups may contain only adult males- with the two highest ranking animals usually unrelated. In groups of the first two types, membership changes if an outsider or a maturing member of the group manages to displace the dominant silverback. Group membership changes also if the dominant male succeeds in recruiting additional females, or when maturing offspring or dissatisfied females leave the group. Brenda Bradley, et al. established that mountain gorilla silverbacks by no means monopolize breeding in multi-male groups (Bradley, 2005, 9418-9423). Females tend to stay in a silverback’s group for protection, both against infanticide by competing silverbacks and against predators. In all male groups, membership changes when any member emigrates, perhaps in search of his own female followers (Dixson, 1981; Fossey, 1983; Harcourt & Greenberg, 2001; Watts,1994; Sicotte, 1993; Robbins, 2001). Chimpanzee groups are clearly male bonded. Males usually remain for life in their native group. Females are prone to leave at sexual maturity in order to avoid inbreeding. If females remain in their native group, as some do, they are likely to leave it temporarily when in estrus. Thus some members of any group are likely to have been sired by males from another group. Despite the limited sharing of genes in such cases, males still bond closely with the group in which they were born. Because chimpanzees are chiefly fruit-eaters and fruit trees tend to be widely dispersed, they usually forage alone or in small groups rather than staying together in one large body. In their foraging, males will call others to the scene when they find a loaded fruit tree. Females, foraging usually in mother- offspring groups and conscious perhaps that the dominant males will take precedence in feeding, do not. Males clearly enjoy the company of other males. They groom each other, for example, more than females do. Males are more aggressive toward each other than are females, but they are also more likely to reconcile quickly. Reconciliation may be marked by extending an open hand, keeping eye- contact, vocalizing softly, and by kissing. All adult males of the group are likely to mate with any female in estrus, although dominant males take precedence when they choose to do so. A male in consort relationship with a female in estrus, a common phenomenon, tries to keep the female away from other males. When he fails, he usually retaliates against the female rather than the interloping males. The purpose served by all this male bonding is to strengthen the group for its struggles with other similar groups. What is at stake in those struggles we shall consider below. Female chimpanzees manifest much less commitment to the group. They often leave it at sexual maturity, although females of the group they attempt to join usually give them a rough reception for some time. Female members who remain with the group of their birth, but join another temporarily when in estrus, are likely to receive a warm welcome by males in the neighboring group, if young and unaccompanied. They are less happily received if older and accompanied by previous offspring. The chief bonds manifested by females are to their own offspring and sometimes to female friends (Goodall, 1986; Waal, 1982, 1989, 1994,1996, 2001a, 2001b; Waal & Tyack, 2003; Wrangham, 1987, 1994, 1996; Wrangham & Peterson, 1996). Bonobos, less well known than the other primates considered, perhaps require some introduction. Chimpanzees, adapting to semi-arid climes, branched off from a common ancestor with bonobos some 2.0-2.5 mya. According to Frans de Waal, bonobo “anatomy is less specialized than is the chimpanzee's. Bonobo body proportions have been compared with those of the australopithecines [4.4-1.8 mya]… When the apes stand or walk upright, they look as if they stepped straight out of an artist's impression of early hominids” (Waal, 1995). This more arboreal and herbivorous species (chimpanzees are prone to walk less, and to hunt other primates much more), is now generally viewed as mankind’s “closest relative" in the animal kingdom (Parry, et al, 14830). It is even claimed that bonobo antigens for group A blood are “serologically indistinguishable” from the human antigen (San Diego Zoo). Nearly identical to chimpanzees in appearance, bonobos are more slender, have smaller heads, finer hair, longer legs, and narrower shoulders- and are most renowned for their propensity to make love, not war. Waal characterized the spectacular ubiquity of their sexual encounters (which, unique among non-human primates, can be face-to-face) as “strikingly casual, almost more affectionate than erotic” (Waal, 1997, 5). He has also noted that bonobos have “a far more sensitive temperament. During World War II bombing of Hellabrun, Germany, the bonobos in a nearby zoo all died of fright from the noise; the chimpanzees were unaffected. Bonobos are also imaginative in play… are incurably playful and like to make funny faces, sometimes in long solitary pantomimes” (Waal, 1995). With groups of bonobos, as with chimpanzees, females tend to leave their native group during adolescence. However, bonobos appear to be “unique in that the migratory sex, females, strongly bond with same-sex strangers later in life. In setting up an artificial sisterhood, bonobos can be said to be secondarily bonded; kinship bonds are said to be primary” (Waal, 1995). Perhaps the major difference between bonobos and chimpanzees is in this sociability of females. Chimpanzee females tend to move alone or in small parties, whereas bonobo females prefer to stay in mixed parties. As a result, bonobo foraging groups are significantly larger than those of chimpanzees. A further explanation, offered by Wrangham and Peterson (1996, 224), is that they live in the rain forest south of the Zaire River, where the lush vegetation and the absence of competing gorillas affords them a very easy subsistence. Chimpanzees, who live in drier climates, in order to forage successfully must often do so alone or in quite small groups. Because female bonobos in their large foraging groups form coalitions much more easily than do males, females generally are able to successfully resist the subordination to males which is the rule among chimpanzees. They appear to do so by exchanging various types of social behaviours- such as genito-genital rubbing, peering, and food sharing- that reduce tension and promote the formation of social associations. Grooming among adults occurs most frequently between males and females, then among females, and least of all among males- a striking contrast with chimpanzees, where male grooming of other males is most common (Nishida & Hiraiwa- Hasegawa,1987; Waal, 1997; Chapman, 1994; Wrangham & Peterson, 1996; San Diego Zoo, 1999; Parish & Waal, 2000). What can be said in summary about group formation and membership among primates? Fundamentally important is that isolated individuals do not do well at either reproduction or survival. In fact individuals expelled from one group almost always make great effort to win acceptance into another group, even though they often experience considerable abuse during a naturalization period. Important for this study is that among monkeys and baboons, males almost always leave their native group at sexual maturity. They usually win naturalization into another group, albeit with some difficulty. Among baboons, males may join a succession of groups. Still more significant is that such naturalized individuals give greater loyalty to the group in which they currently reside than to that of their birth. They will in fact fight alongside its members against the group of their birth. For bonobos and chimpanzees, on the other hand, males do not normally leave their native group. Chimpanzee males are very closely bonded to each other, even those sired by males from another group. We turn now to examine group formation and membership in social carnivores. Lion prides generally consist at the adult level of female siblings and their female descendants, plus one or two mature males unrelated to the females. Prides expel maturing males who then live as nomads, sometimes as pairs of brothers, until they can drive off and replace the male(s) of a pride other than the one in which they were born (Schaller, 1972; Packer, 1990; Pusey & Packer, 1994; Kruuk, 2002). Hyena groups are similar to those of lions, but with some basic differences. At the adult level, permanent group members among spotted hyenas (the most numerous variety) are female siblings and their female descendants. Adult male hyenas, unlike their lion counterparts, are slightly smaller than females and subordinate to them. Adult male members of a group are those expelled from their native groups at sexual maturity who have since won acceptance by another group. The naturalization period is usually long and difficult. When prey is sparse and widely diffused, hyena groups often break up. Smaller groups or even individuals then tend to forage by themselves (Henschel & Skinner, 1991; Jenks, 1995; Kruuk, 1972; 2002; Mills, 1990; 2001; Mills & Hofer, 1998; Drea & Franks, 2003). African wild dogs, like chimpanzees, live in tightly knit, male-bonded groups. Females leave the group at sexual maturity. Together pack members can kill prey much larger than the dogs are and indeed such animals are their usual fare. No dog alone could have such success. Group solidarity is clearly evident in the rallies preceding a hunt when enthusiastic greetings and other encouragements work up spirit for the endeavour (Lawick-Goodall, 1971; Sheldon, 1992; Creel, 1995). Wolf packs are almost always family affairs, an alpha male, an alpha female, and their offspring. Even more than lions and hyenas, they clearly derive much emotional satisfaction from associating with other group members, and indeed all pack members will help to raise the alpha female's pups. Maturing individuals usually tire in time of subordinate status and a non-breeding role in their native group. If unable to replace the alpha parent of their sex, they are likely to abandon the group in the hope of linking up with another such individual from a different pack to start a new one (Mech, 1988, 1998; Klinghammer, 1979; Frank, 1987; Hall & Sharp, 1978; Fox, 1975, 1978; Zimen, 1982; Sullivan, 1978; Savage, 1996). So much for group formation and membership among non-human primates and social carnivores. Now we turn to prehistoric humans. For our purposes they may be divided into three simple categories: hunter-gatherers, crop-growers, and nomadic herders. What patterns can be discerned in each of these groups with reference to group formation and membership? Modern humans, homo sapiens sapiens, had spread over most of Africa, Australia, Europe, and Asia as hunter-gatherers by about 50-45 kya. From then until now, our species has experienced no major biological modifications (Fagan, 2001; Foley, 1995). If there are hereditary factors influencing human behavior as it relates to the formation of groups and the rivalry among them, it seems reasonable to expect that those factors would be evident in the behavior of those who lived by hunting and gathering. All of our ancestors lived in essentially that pattern for roughly 90 percent of modern humans’ evolution (from c.72 kya). What then was the pattern of group formation and membership among hunter-gatherers? Obviously hundreds of thousands of very adaptable people inhabiting every land region of the globe, excepting only Antarctica, and living in sovereign groups which averaged about 30 members each are not likely to have conformed to a single pattern of behavior. Furthermore, most such groups vanished long since without leaving much recoverable (or at least yet recovered) evidence as to how they behaved. However, a few groups on several continents still live in a hunting-gathering pattern today, or did so when observed by anthropologists. Modern hunter-gatherers may well not reliably reflect the behavior of those who lived long ago. They have a much narrower choice of habitat, because population has expanded exponentially and modern people have reserved the best land for organized economic activities. The !Kung San groups of the Kalahari desert studied in Richard B. Lee’s famous work (1979) averaged 31 members. They were originally very strict about exogamy, but ambivalent about which sex left its native group. Before a young man's family could arrange a marriage for him, he had to have established his skill as a hunter to the satisfaction of the bride's family. Then he joined her family for several years of "bride service" after which the couple might return to his family, stay with the bride's family, or go elsewhere. From this and other evidence, it appears that !Kung San groups were eager to recruit members- especially good hunters, and that moving from one group to another was relatively easy. Indeed, Lee observed that most of the !Kung San lived in groups other than the one in which they had been born. This is not at all unusual. Even the simplest societies, such as the !Kung, Joseph Henrich asserts, “have quite strong institutions for maintaining cooperation on a scale much larger than the family or the band (Wiessner, 1983)... contrary to the view of foraging created by anthropologists studying extant groups, lots of archaeological and ethno-historical data indicate that foraging societies can be politically, economically and socially complex, with large-scale cooperation, social stratification and a substantial division of labor” (Henrich, 2004, 19). He adds that “the fact that the between-group component is what drives reciprocity is often lost because it is substantially easier to solve this problem using the ‘individual fitness-accounting’ approach” (Henrich, 19). Unique as some practices of the !Kung San surely were, other studies- including some quite critical of Lee- tend to confirm that major features of their culture were typical of hunter-gatherers. Groups exercising sovereign power were quite small. Maturing females usually left their native group for another, although as with the !Kung San this practice could often be modified to require males to leave their native group, at least temporarily in order to secure a bride. The basic point, however, is that a substantial proportion of the members of any group would always be people who were born in another group. Furthermore it appears that moving from one group to another involved substantially less trauma than is usual for other primates or for social carnivores (Price & Brown, 1987; Ingold, 1988; Smith & Winterhalder, 1992; R. White, 1991; Boehm, 1999; Fagan, 2001; for citations to dissenters, see R. Lewin, 1988). Furthermore “a substantial amount of work in psychology and behavioral genetics” shows that, even when not subject to switching groups, children "do not acquire much, via social learning, from their parents” (Harris, 1998; Plomin et al., 2000; as cited by Henrich, 20)- as many of us with experience parenting (or being) teenagers can attest. The village culture matters. The !Kung, popularly known as the "harmless people," were also typical of hunter-gatherers (or at least more recent hunter-gatherers) in their propensity for homicides. Lee himself reported in his studies (1979, 398; 1982, 44) that from 1963-69, there were 22 murders- making for a homicide rate roughly twice as high as that for almost any country in the world. It had been even higher before (Gat, 2000a, 15). Most other hunter-gatherer societies of today, from Eskimos to the Yanomamo, also have unusually high murder rates. They also have a relative scarcity of females, in comparison to sovereign nations (14-15). It is still unclear as to when such sex-ratios and murder rates became prevalent in most hunter-gatherer groups. Perhaps men living in ecologically dominant, yet small egalitarian hunter groups, would, not unlike lion pride members (see below), rather risk their life than become subordinate and lose face to someone else. Hunter-gatherer violence, however, was almost certainly common by the time complex hunter- gatherer societies, which tended to be more sedentary, started to appear during the dozen or so millennia of transition from hunting and gathering to predominantly agricultural subsistence. Complex hunter-gatherer societies typically did not migrate within a broad home range as did simple hunter- gatherers, but located permanently in an area in which food was naturally abundant. Such people began the series of changes in the pattern of group formation and membership which would become much more pronounced with the development of agriculture, to which we now turn. Mark Nathan Cohen (1977,1984, 1989), among others, found many indications of increasing subsistence problems for hunter-gatherers during the transition period. Among them were greater skeletal evidence of malnutrition, increased utilization of small animals and birds rather than the preferred large ungulates, increased reliance on plant foods, including those requiring difficult preparation, more attempts to preserve and store food for future use, and greater environmental degradation brought on by excessive human exploitation. Several contributors to Price and Gebauer (1995) dispute Cohen’s contention that the pressure of increasing population almost required the invention of agriculture, but others, including Mears (2001) as well as Stiner (2002), and Ungar and Teaford (2002), endorse it. Whatever the explanation, domestication of both plants and animals followed rather quickly on the development of complex hunter-gatherer societies. The earliest widespread domestication of both plants and farm animals occurred in several areas of the Southwest Asia about 10,000 years ago. Diffusion of agricultural practices within the region and from Southwest Asia to adjacent areas clearly did take place. However, it is also clear that by about 7000 years ago domestication had arisen independently in both China and the Americas. In subSaharan Africa, where hunting and gathering had continued to work well and where there were far fewer domesticable species, extensive domestication came somewhat later. Reinforcing the argument that expanding human population drove the invention of agriculture is the evidence that agriculture did not provide a better way of life. The nutrition of the agriculturalists' diet was typically inferior to that of hunter-gatherers. Among agriculturalists human stature (and brain size) also decreased. Labor requirements were much higher and the dependability of the food supply generally lower. There were also problems in protecting the harvest from spoilage, from rodents, and from plunder by other groups. What led to the widespread adoption of agriculture in the face of these problems would appear to have been necessity. The only alternative to agriculture for a growing human population was greatly intensified competition with other groups for possession of the large territory required to sustain a hunting-gathering way of life (Cohen, 1989; Eaton, 2002; for alternative explanations, see Fagan, 2001, 232 ff). Crop-growing and the domestication of animals intensified the pace of the changes begun with the appearance of complex hunter-gatherer societies. Groups became still larger, because in favorable areas agriculture- despite the deficiencies in diet- could sustain far more people on the same amount of land than could hunting and gathering. Large size was also necessary to protect the group's resources from appropriation by outsiders. Outsiders indeed came to be regarded as potential threats, not only to stored food resources, but even to possession of the land. Ritual symbols of group membership proliferated (Cohen, 1977, 67). Because groups were now large enough to obviate the problems of inbreeding, endogamy replaced the traditional exogamy of hunter-gatherers. Group membership became closed. Outsiders were much more likely to be perceived as threatening (Cohen, 1977, 1984, 1989; for other accounts, see Harris & Hillman, 1989; Harris, 1996; Henry, 1989; Rindos, 1984; Reed, 1977; Maisels, 1990, 1993; MacNeish, 1992; Fagan, 2001; Ungar & Teaford, 2002; Mears, 2001). Nomadic herders of newly domesticated animals (sheep, goats, camels, cattle, and horses in particular) were different from the settled agricultural people. For sedentary agriculturalists, the tending of livestock was generally subordinate to cultivating fields. Nomads, however, lived in marginal areas "too dry, too elevated, or too steep" for crop cultivation to be practicable (Johnson, 1969, 1). While no one knows precisely how nomadic herding came to predominate in such areas, there is some suspicion that it evolved naturally from transhumance- the seasonal movement of domesticated animals to different pasture areas as practiced by sedentary farmers. Repeated crop failures experienced by farmers in marginal areas may have led them to decide to rely more fully on their animals for a livelihood. In any case, nomadic herders were low status people, disparaged by the more numerous sedentary farmers, and often desperate to secure supplemental items for their subsistence, which only the sedentary communities could supply. Nomads secured these items by various means. These included trade, plundering raids, and extortion of contributions for "protection." Sometimes they succeeded at conquering and subjugating groups of farming people. Group membership originally derived basically from kinship. The herding unit comprised usually a few related families, although unrelated individuals frequently lived with such groups. These families owned individual animals, which grazed in a communal herd. In most nomadic societies, men married outside the group. They might (as with the !Kung San) go through a period of bride service with the bride's family, but the new couple's permanent affiliation would normally be with the man's group. Groups were generally quite unstable, as any discontented family could take its livestock and leave. Changing weather conditions also could lead to either the aggregation of several related groups in wet periods, or the splitting of one group into several groups in times of drought. For purposes of raiding or the exaction of a protection price from farmers or traders, somewhat larger coalitions might form. Such groups often had a tribal basis, with a leader traditionally chosen from the same respected family. Conquering groups of nomads usually had individual leaders whose authority was charismatic in character (Cribb, 1991; Gamble & Boismier, 1991; Goldstein, 1990; Johnson, 1969; Tapper, 1979; Casimir & Rao,1992; Golden, 2001). Group Formation and the Social Sciences We now detour briefly from animal behavior and early humans to consider what the social sciences may contribute to helping understand the formation of groups and membership in them among modern people. The fields to be considered include: 1) history, 2) political science, 3) sociology, 4) psychology, 5) social psychology, and- last but not least- 6) anthropology. Geography and economics will receive attention chiefly in conjunction with historical experience (national case studies), to be considered in latter sections of this book. As each of these fields tends to overlap all the others, we shall make only an introductory effort to consider each separately. Obviously, this is a highly selective process, choosing to consider only those propositions that appear to be of fundamental importance to understanding the phenomenon of nationality (ancient) and national identity (modern) in our species. First, a few observations about scope and method in the social sciences may be useful. The term "social sciences" invites comparison to the physical sciences and has come to carry the implication that these fields of knowledge should emulate the spectacularly successful methods of the physical sciences, particularly the emphasis on rigorously controlled and replicable experiments. History of course does not lend itself to the experimental method. Controlled experiments cannot be done (or at least should not be done) with the large groups of people with which historians are usually concerned. They certainly cannot be done retroactively, that is under conditions and with people that have long since disappeared. The German scholars who first professionalized the study and writing of history in the late 19th century nevertheless were prone to advocate “scientific history.” The historian, they argued, should see the mission of the profession as to find and report facts, the more the better, with scrupulous objectivity and no interpretation. Many narrative historians still write in that tradition. Others, while still assiduous in pursuit of facts, tend to view the idea that they should eschew interpretation in the interest of scientific objectivity as an intellectual curiosity peculiar to the founding fathers of the profession. History in any case is surely the least "scientific", or theorized, of the social sciences. Indeed many practitioners, especially the narrative historians, prefer to link it to the humanities rather than to the social sciences at all. History does have the advantage, however, of being more comfortable than most of the social sciences in dealing with large groups of people. In fact, until relatively recent times history was most often written in a national context, and with much attention to rivalry among nationalities. Consequently, there is a vast volume of nationalist-inspired historical literature focusing on contending nationalities. Political science, as the name suggests, attempts to honor the scientific ideal. Indeed, many of the leading journals in the field carry the term "science" in their titles. Like historians, political scientists also often deal with rather large groups that do not lend themselves easily to controlled experiments. They tend to concern themselves with power rivalries among groups. However, with the notable exception of international relations scholars, they tend to focus more on power struggles within nationalities, rather than on those between them. Furthermore, their contemporary as opposed to historical perspective leads them usually to take nationalities as a given, rather than to feel compelled to account for their development. Political scientists, like so many other academic writers, sometimes follow the “weather-vane,” in the sense that they flock to subjects currently in the headlines. In the period of "nation-building" following World War II, political scientists lavished attention on that subject with highly useful results. Since the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia into sovereign ethnic entities, however, inter-ethnic relations have become the focus of much writing by political scientists. Sociologists study groups, but they have traditionally preferred to study small rather than large groups, often by controlled experiments or by personal observation or questionnaires. The Handbook of Sociology (Smelser, 1988) had one paragraph on "national identity," but no indexed references to nationality. A growing number of sociologists, however, have come to focus their attention on ethnicity and nationality. Indeed many of the most widely cited authors on nationality and nationalism, e.g. Anthony D. Smith, Liah Greenfeld, and Charles Tilly, are sociologists. As Tilly observed, the interest of his fellow sociologists “is to specify the general processes involved…" in forming a national identity (Tilly, 1981, 5). In addition to the usefulness of such sociological work in building an understanding of ethnicity and nationality, much of what sociologists have found concerning small groups seems highly applicable as well. Psychologists study individuals, and of all social scientists are the most devoutly committed to the methods of empirical science, especially to rigorously controlled and replicable experiments. Carl Murchison protested in 1935 that this commitment had led to a preoccupation with "trivial, superficial, damnably unimportant topics" (Quoted in Lindzey, 1985, I, iii). Gordon Allport lamented the same tendency in the 1968 edition of The Handbook of Social Psychology (Allport, 1968, I, 69). "Aid in solving major social problems,” he observed, ”is unlikely to come from small, gem-like researches however exquisite their perfection." His plea for a return to grand social theorizing fell on deaf ears, however. In the 1985 edition, Allport repeated his plea (Allport, 1985, 41 f). Meanwhile R.B. McCall (1978) had complained that the "experimental method now dictates rather than serves the research questions we value, fund, and pursue." Ellen Berscheid (1992) noted that during the previous quarter- century the study of humans, as opposed to rats, had become much more respectable in psychology's search for universal patterns of behavior; but that the grand theorizing which Allport longed for was still hard to find. Essays which would have warmed Allport’s heart appeared, however, in the 1998 edition of the “Handbook.” Philip E. Tetlock asked if social psychology was of any help in understanding war and peace among nations. Noting that there was much disagreement among authorities on how to answer that question, he then attacked “neorealists” for asserting that a nation’s “decision-makers must act like egoistic rationalists” whom he characterized parenthetically as “calculating psychopaths” (Tetlock, 1998, 874). Also encouraging was the appearance in 2001 of a book titled Self and Nation, written by two social psychologists, Steve Reicher and Nick Hopkins. They observed that “the social power” of nations “is often noted, frequently taken for granted, and never explained” (Reicher & Hopkins, 2001, 26). They calculated as well that between 1987 and 1994 journals on social psychology published 3174 articles on rats, 485 on personality characteristics, and 19 on national identity or nationalism. Thus Allport’s desire is still some distance from fulfilment. Significant also is the observation that even social psychology, presumably a meeting place of sociology and psychology, has come to be dominated by psychologists (Jones, 1985, I, 47). Consequently it tends to show much more interest in individuals than in groups. Indeed even Allport defined the mission of social psychology as "to understand and explain how the thoughts, feelings, and behavior of individuals are influenced by the actual, imagined, or implied presence of other human beings" (Allport, 1985, I, 3). Another definition of the field states that its concern is "the study of individual behavior in social contexts" (Taylor & Moghaddam, l987, 3). European social psychologists, complaining of what they considered excessive focus on individuals by their American counterparts, produced a body of literature addressed much more to group behavior (see, for example, Israel & Tajfel, 1972; Turner, 1984, 518). Even in the European work, however, one rarely encounters the word "nationality." Despite these reservations, the work of psychologists, especially social psychologists, affords much information of great utility for the study of nationalities. Anthropology has already received considerable consideration earlier in this chapter, but a few observations on the field as a whole are perhaps warranted. Some time ago, anthropologists- who often state that they study society from the bottom up- lavished attention on "national character" in an effort to identify what was distinctive about the people of different nationalities. In the latter 20th century, a trend tended to attribute a “primordial” quality to ethnic identities, and to slight national identities of what many now call a civic character. Nevertheless, as we hope the preceding sections have shown, anthropologists have produced highly useful information on patterns of group formation and relationships between (and within) groups- in addition to thoughtful explanations of social evolution and the brain. Conclusions on Group Formation What then is to be learned from the work of social scientists regarding human conduct in the formation of groups and membership in them? Surely the most basic lesson is that we are social animals. We need almost as desperately as monkeys to belong to groups. Social psychologists Muzafer and Carolyn Sherif expressed this need cogently: ' One of the strongest promptings of human beings is to establish stable, secure social ties with ' others... to have a dependable anchor for a consistent and patterned self-picture which is essential for ' personal consistency in experience and behavior, and particularly for day-to-day continuity of the persons' self- ' identity. Some stability of social ties is a prerequisite condition for the individual to experience himself (sic) as ' the "same person" from day to day, with his (sic) characteristic attributes and moorings. There is very ' considerable evidence that lacking such ties, the individual has great difficulty in establishing a clear ' self-identity, and that, once developed, the absence of such ties promotes experiences of estrangement and ' uncertainty, accompanied by erratic and inconsistent behaviours (Sherif & Sherif, 1964, 270). Ellen Berscheid was more succinct in affirming that "absolute social isolation can be devastatingly painful and produce… hallucinations, extreme apathy, and, frequently, severe anxiety" (Berscheid, 1985, 443). What seems likely from these and other similar observations is that humans are genetically programmed to live in groups or, to put the point another way, that those not so programmed have died out. As with so many of the animals considered above, living in a group enhances one's prospects for survival and reproduction; living in isolation impairs them. This helps explain why individuals tend to conform to group norms and to obey group leaders, even to the point of doing physical harm to others against whom they have no grievance. As Moscovici put it: "The possibility of being excluded from the group induces most people to become more like the other members of the group and to avoid becoming deviant" (Moscovici, 1985; see also Milgram, 1974; Blass, 1991). Group intolerance of deviant behavior seems to reflect concern to avoid fragmentation and weakening of the group. Indeed actions perceived as treasonable or threatening the very existence of the group are those most likely to evoke a swift and severe reaction (Moscovici, 1985; Sherif & Sherif, 1964, 265; Gove, 1980; Goode, 1990; Prus & Grills, 2003). The smallest of the various groups to which humans normally manifest their belonging is of course the family. Basic to it are the bonds between mother and child, between father and child, the male- female pair bond, and the bond between siblings. Beyond those bonds of the nuclear family are those of the extended family, which typically include grandparents, uncles, aunts, and cousins. Beyond the extended family lies what for the purposes of this study can be called the ethnic group. In its most pristine form, it consists of a considerable group of people who are, or at least believe they are, descendants of common ancestry. Quite often common ancestry will have imparted to group members distinctive physical features: facial configuration, body-type, color of eyes, hair, skin, etc. Such features help to make group members easily, although not infallibly, identifiable. Quite commonly too, the isolation from other groups which permitted physical distinctiveness to develop will also have created cultural distinctiveness, especially in language and religion. Some devotees of the ethnic conception of nationality have tended to regard such ethnic groups as "primordial," suggesting not only that they arose very early, but that the natal bond to them is somehow unseverable. The second of those assertions, to reiterate, is untenable. The culture or community one lives in, moreover, is not necessarily limited to self-identified ethnic conspecifics, as we hope the preceding chapter has made clear. Indeed, modernity and prosperity both seem to be forces for civicly tolerant (as opposed to ethnically discriminatory) societies, and any emergent global civil society would also have to be the same Anthropologists in particular may wonder why we have thus far avoided the widely used terms band, tribe, chiefdom, and state, which Elman Service (1962, 1971; see also Renfrew & Bahn, 2000) adduced to differentiate the evolving forms of organization in human groups. Band correlates reasonably well with what we have preferred to consider the “extended family”, sometimes called 'clan'. A tribe is a coalition, usually in excess of 100 members, of a number of extended families; whereas a chiefdom is a confederation or political alliance- typically under charismatic leadership- of tribes. To avoid any confusion, we prefer to categorize merely as “ethnic groups” those people organized purportedly along kinship lines in groups larger than extended families, but not yet sufficiently organized to be called states (see chapter 3). Not so widely recognized as the kinship basis for groups is a tendency for human groups also to be male-bonded. As with chimpanzees, bonobos, and wild dogs mentioned above, it is the males of the human species who seem genetically programmed (for references and qualifications, see below) to stay in their native group. It is the females who typically leave at sexual maturity. This evolutionary adaptation to the unhealthy consequences of inbreeding and the advantages of genetic diversity thus complicates the simplistic picture of group formation based largely on consanguinity. Because of the inherent tendency to avoid incest, men and women in pair bonds tend to come not only from different nuclear families, but often also from different clans. This disposition to avoid incest stems from our genetic makeup (Fox, 1980; Shepher, 1983), as it appears to do in the other animals we have considered. It helps to explain why in many instances individuals lacking genetic ties to the group in which they reside will nevertheless manifest strong loyalty to it. While human males in particular are usually reluctant to abandon their native group, evidence presented above and to be elaborated below, makes very clear that in some circumstances they do. It is also clear that when their naturalization into another group is complete, usually after a considerable period, they will generally give greater loyalty to their new group than to that in which they were born. Like the other animals considered above, they may even fight as members of their new group against their native group. Thus it is important to recognize that even for males the bond of common ancestry is by no means unbreakable, and that people of either sex can give greater loyalty to a group into which they have been naturalized than to that of their birth. This is in some measure merely a restatement of Kurt Lewin's "interdependence of fate" argument in Resolving Social Conflicts (Lewin, 1948, 184). Lewin, who migrated from Nazi Germany to Britain and then the US in the 1930s, pointed out that similarity of group members, whether genetic, cultural, or both, is less important as a basis of group solidarity than is the recognition of how members depend upon each other, perhaps even for their very survival (see also Billig, 1976, 332). Some twenty centuries earlier, it may be noted, “Master Lu's Spring and Autumn Annals” (the Lushi Chunqiu) made much the same point in soon-to-be-unified China. Among its justifications for a multi- ethnic unifying state are 1) “Political order was not created out of a ‘state of war’, but rather the people were brought together because of mutual benefit…” (Sellmann, 1999, 203); 2) “The fact that the masses can gather together is because they benefit each other” (203). What else should we know about how modern humans form groups and determine membership in them? More than a century ago William Graham Sumner made the famous distinction between in- groups and out-groups (Folkways, 1906). Social psychologist Warren G. Stephen, expanding on Sumner’s observation, noted that "mere division of people into groups leads to biased evaluations of the groups… and to discrimination in favor of in-group members and against out-group members. The research in this area indicates that virtually any [italics added] categorization process can lead to in- group out-group bias" (Stephen, 1985, II, 6l3). John C. Turner asserted similarly that "social categorization per se is sufficient for intergroup discrimination and the minimal conditions for group formation do not seem to include cohesive relations between members or any degree of interdependence" (Turner, 1984, 524). Turner went on to expand on what authorities on deviant behavior have called the labeling phenomenon: that people tend to take on identities attributed to them. "It seems,” he noted, “that psychological group formation can take place purely through external designation" (526; cf. Billig, 1976, 335, 357; Gove, 1980; Goode, 1990; Prus & Grills, 2003; Reicher & Hopkins, 2001). Social identity theorists have produced other ideas relevant to group formation. Individuals, they assert, strive for a positive social identity. One way people can attain that goal is to abandon a low status group for one of higher status. When such a transfer of membership cannot be brought about, the dissatisfied members are likely to “pursue status improvement collectively.” If they perceive their group’s low status to be a product of unjust treatment, that perception still further “strengthens ingroup identification” (Van Knippenberg, 1993). In other words, a group’s perception of its own low status may foster solidarity. It may also provide incentive to seek sovereignty, in order to elevate the group’s status and to mobilize the group’s resources for the pursuit of still higher status. How much status is enough to satisfy an individual or group? These questions have not yet been adequately answered, at least in terms of group status; although a number of prominent 20th century psychologists (Maslow, Erikson, Horney, Rogers, Kelly, Bruner) would appear to have resolved the matter at least in terms of modern individuals. Perhaps large groups, and even nations- which can be viewed simply as aggregations of individual psychologies- will in time follow the lead of prominent individuals and become less egocentric. Social psychology appears to offer several other suggestions about group formation and membership. People are attracted to groups whose members are more like them in appearance and customs, a finding reinforcing the importance of ethnicity as a basis of group formation. On the other hand, they feel closer to dissimilar ingroup members than to similar outgroup members (Turner, 1981, 79), which would seem to reinforce the civic. Basically people are attracted to groups (either ethnic or civic in character) that esteem them highly and help them attain personal goals. Conversely, they become alienated from groups which do not esteem them highly or frustrate them in their pursuit of personal goals. As Muzafer and Carolyn Sherif put it: "individuals… form new groups when old groups… become obstacles rather than instrumentalities for the essentials of living" (Sherif & Sherif, 1964, 272). People also feel more strongly attracted to their group when it is threatened by or in competition with another group or groups. To a considerable extent, members, particularly males, take their identity and in some contexts their status from that of their group. They take on its stereotypical characteristics. They exaggerate how much they are like ingroup members and different from outgroup members. They are also likely to exaggerate their superiority over outsiders (Brown & Turner, 1981, 39; cf Reicher & Hopkins, 2001). Particularly important for this study is the classic work of Muzafer Sherif et. al, Intergroup Conflict and Cooperation: The Robbers’ Cave Experiment (1961). Sherif's work demonstrated how random division of adolescent boys into competing groups tended to produce intense intergroup hostility. He then showed as well how the emergence of a superordinate goal, a common interest of overriding importance to all the competing groups, could lead them into harmonious cooperation. Later, to much less acclaim, Sherif sought to apply these finding to international relations in a book titled: In Common Predicament: Social Psychology of Intergroup Conflict and Cooperation (Boston, 1966). Designated "Realistic Conflict Theory" by subsequent admirers, Sherif's ideas became the basis for extensive research on how groups relate to each other (Taylor & Moghaddam, 1987). Theories of revolution also have bearing on group formation. Aristotle's observation that inferiors become revolutionaries in order to become equals is a reasonable starting point (Barker, 1946, 207). His identification of inferiors as potential revolutionaries seems unassailable. Evidence about dominance struggles in other animals as well as in humans makes it appear unlikely that mere equality is the goal of revolutionaries. They seem more often than not to seek superiority, to become dominant in place of their oppressor. "Relative deprivation theory," a more recent attempt to explain revolutions, puts a similar emphasis on the rival relationship among groups. Devotees of this idea (also sometimes referred to as unfulfilled rising expectations) suggest that it is the status of one's group relative to that of another group which is important in providing motivation for revolution, not any objective measure of deprivation (Gurr, 1968; 1970). For example, during the US civil rights era, the most serious riots occurred not in the geographic “areas of greatest poverty but in Los Angeles and Detroit, where things were not nearly as so bad for African-Americans” as in most other large urban centers (Aronson, 2005, 401). These observations stressing the importance of rivalry in relationships correlate closely with that of the political scientist, Rupert Emerson. Emerson first cited Jawaharlal Nehru's observation that "Nationalism is essentially an anti-feeling, and it feeds and fattens on hatred and anger against other national groups" (Emerson, 1960b). Emerson then affirmed that "Reduced to its bare bones, nationalism is no more than the assertion that this particular community is arrayed against the rest of mankind" (1960a, 213). It is important to remember, however, that recognition of common interests, unrelated to external rivals, can also be a significant influence on the development of a new national identity. Two other observations from the social sciences on the emergence of new nationalities seem especially important. Both stem from the work of Edward Shils. In studying the development of new nations after World War II, Shils concluded that "Distant authority is 'alien' authority. Even when it is ethnically 'identical' with those over whom it rules, this 'alienation' exists in those societies which are used to being ruled by visible and proximate authorities" (Shils, 1960). Thus in some circumstances, geography alone can apparently give rise to a sense of separate identity and the desire for sovereign authority based on that identity. Edward Shils also drew attention, at least obliquely, to frequent conflict in the formation of new nationalities, between what we may call the “outward-looking elite” and the “inward-looking masses”. The elite, especially in colonial situations, often seek to remold their society in the image of an admired foreign model, usually that of the imperial power. They do so not only out of admiration for the foreign culture, but also in order to enhance the international prestige of their own group by making it more nearly like the widely respected model. The inward-looking masses, on the other hand, tend to be less aware of and less concerned with international status. They are usually tenacious in defense of their traditional culture, and hostile to the foreign culture which members of their own elite find so appealing. Creating new national identities, as will be observed more fully in later chapters, has often involved conflict between these two opposing preferences (Shils, 1957; 1960; 1972). Charismatic leadership and its effects also require particularly close attention. It is a fundamental assumption of this book that people (given enough population density/economic scarcity) have always formed rival groups, which have often been based on predominantly kin-ethnic or territorial-civic considerations. If that contention is to have credibility, it must be supported by an explanation as to why, for long periods in many parts of the world, large groups of either the ethnic or the civic variety have been conspicuously absent. The phenomenon of charismatic leadership affords at least a partial explanation. In popular use, charisma focuses on the qualities of a leader, qualities which make the leader appear to followers as possessed of extraordinary or even supernatural power. Max Weber, who first popularized the term, observed that there were several ways in which charismatic authority, either revolutionary or traditional, could be institutionalized. For example, it could be institutionalized in a hereditary monarchy perceived as divinely sanctioned, in the papacy, or even in an office such as the American or French presidency. He noted also that charismatic authority flourished when it brought success in serving the needs of the people, but tended to dissipate with the perception of failure. Other students of charisma have emphasized how much charismatic authority depends upon the existence of stress or a sense of crisis among the people (Weber, 1968; Eisenstadt, 1968; Shils, 1975; Lindholm, 1990; Willner, 1984; Glassman 1984; Lepsius, 1986; Smith, T. 1990; Breiner, 1996; Popper, 2001). The key suggestion from our proposed curvilinear relationship between stress and affiliative tendency (Fig. 1:1) is that high and continuing stress would, at some point short of panic, be expected to foster in virtually all people feelings of dependence upon a charismatic leader and/or institution (Schachter, 1959). Such conditions would also diminish feelings of identification with any large group, in preference for individual survival and safety. These, according to Albert Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, are the most dominating needs within any individual who lacks them (Weiten & Lloyd, 2006, 54). Relationships of charismatic dependency have provided an alternative to nationalities of either an ethnic or civic variety throughout much of human history. With the advent of printing, increased literacy- and more recently of mass telecommunications- national leaders have at times exploited crisis conditions, real or invented, to reinforce their own authority and/or their society’s national identity. Hitler’s Nazi Germany perhaps illustrates these tendencies most clearly in modern times. Max Weber originally outlined three ideal types of legitimate political domination: 1) personal or ”charismatic authority”, 2) “traditional authority” (including patriarchy, patrimonialism, and feudalism), and 3) the rational or “legal authority” typical of Western capitalism (Weber, 1968b, 46). There appears to be considerable overlap between the first two of these three categories in particular- primarily the tendency of charismatic mobilizations or revolutions to devolve into more traditional institutions of personal dependence over the longer-term, once the charm of a certain individual has passed. Weber’s concept of charisma appears to have much in common with his concept of patrimonialism, wherein “the official has a personal dependence on the ruler” (Antoni, et al, 1998, 78). Moreover, the “bureaucracies which sprang up around the patrimonial ruler were unlike the bureaucratic systems which developed in rational capitalism. Political decisions and procedures were not so much rule-following as based on the personal, arbitrary decisions of the ruler…. [giving] rise to a peculiar combination of rigidity and unpredictability...” (79). In Weber’s own words, the patrimonial state “created a realm of unshakable sacred tradition alongside a realm of prerogative and favoritism” (Antoni, 79). It would appear that Weber’s definition of ‘charismatic authority’ is what we would merely call an individual charismatic leader; whereas his explanations of traditional patrimonialism are more in line with what we term authoritarian or charismatic-justified institutions (the use of force in politics is often justified with appeals to the sacred and religious). In any event, Weber himself was aware of his trichotomy’s limitations, indeed writing that “the idea that the whole of concrete historical reality can be exhausted in the conceptual scheme about to be developed is as far from the author’s thoughts as anything could be” (Weber, 1968b, 47). Undeterred however, in all the chapters which follow we shall consider not only the fascinating phenomenon of charismatic leadership, but also the policies that often follow in its wake- examining how at times 1) individual charismatic leadership (mobilization) has contributed to the rise of new national identities; how 2) institutionalized charismatic authority (CHA) has often led to the weakening and dissolution of a kin-ethnic or (more often) territorial-civic based national identity; and how 3) charismatic dependency (CHD) has, in times of state weakness or anarchy, often substituted for the absence of salient civic or ethic identity (see more in chapter 3). Dependence upon charismatic leaders and the authoritarian institutions that often follow them may help also to explain what biological anthropologist Christopher Boehm (1999, 88) referred to as one of the great mysteries of social evolution. That is how egalitarian practices, such as prevailed among our hunter-gatherer forbears, evolved into hierarchical practices resembling those of our primate relatives after the development of agriculture. Countless other scholars would probably agree that, in the words of political scientist Azar Gat: “once humans evolved agriculture, they set in train a continuous chain of developments that have taken them farther and farther away from their evolutionary natural way of life…. Human society has been radically transformed and staggeringly diversified” (2006, 145). The following is at least a simple explanation to Boehm’s question. As population densities and trophic pressures increased, something of a demographic vicious circle kicked-off, which is unfortunately still characteristic of many parts of the world today. With increased sedentarism, population growth- already substantial during the increased child survival rates of the late Upper Paleolithic (Stiner, 2002)- typically increased even faster, due to both higher birth rates and higher social value being placed on large families (or at least upon fathers having many sons). With the gathering-to-agriculture transition, women tended to contribute a smaller share of the economy, and were valued increasingly for their reproductive abilities. Given that most sedentary societies already had sufficient babies and children, women’s status tended to decrease with these developments. Female infanticide was widely practiced in many societies. It is all too rarely noted that such practices upset the gender balance and lead to a tradition of surplus males. Gat asserts, however, that even among 20th century hunter-gatherers, juvenile “sex ratios averaged 127:100 in favor of boys (Divale & Harris, 1976). Archeologists have found “similar ratios in favor of males… among the skeletons of adult…Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers…” (Gat, 2006, 74-75). With the greater status differentials of sedentary society, however, increased polygamy- often perfectly acceptable for anyone who could afford it- further contributed to “women scarcity” and “increased men's competition for them” (75). Could it be that there were often at least twice as many eligible men as eligible women in Mesolithic and Neolithic societies? If so, it is easy to see how an Upper Pleistocene ‘land of milk and honey’ could have been transformed over the course of ten or so thousand years of fundamental economic, demographic, and cultural change into Thomas Hobbes’ proverbial “life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (Hobbes, 1914). Simply put, in favoring male offspring over female, “the rational choice of each family when left to its own conflicted with the common good” (Gat, 76). ' text* copyright 2008 Philip L. White and Michael L. White |