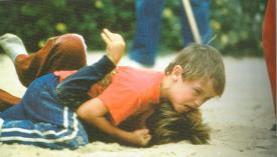

| CHAPTER TWO WHY DO PEOPLE CREATE NATIONALITIES? SECTION B Dominance We turn now to dominance. In most groups of monkeys, dominance is clearly of enormous importance. In multi-male groups, adult males fight, sometimes to death, for dominance. Losers who survive, as is usual in such struggles, may leave the group. Dominant individuals take precedence in feeding and breeding. They also receive frequent displays of deference and generally are the center of the group's attention, especially in time of danger. They may perform both protective and policing functions for the group, as well as exercising leadership. Subordinates accept instruction from them readily, but they are much slower to learn from those of lower rank. In an interesting study, Michael Nader, et. al have found that “dominant monkeys' enriched lifestyle- more treats, more freedom to move about the pen, and more grooming from subordinate monkeys- boosts the number of dopamine [italics added] receptors in the brain… [suggesting] that the increase in dopamine receptors makes the animals less vulnerable to the reinforcing effects of cocaine” and possibly other artificial drugs (Kuchin, 2005, 2953). With females, status is less contested and frequently follows that of the mother. Subordinate females are frequently prevented from mating and experience a relatively high rate of infant mortality, sometimes from infanticide. In times of food shortage subordinates, whether male or female, are usually the first to die. They are also the most likely to leave the group. For our purposes it is also highly significant that larger groups generally assert dominance over smaller ones (see sources cited above for monkeys). Dominance among baboons is similar to that among other monkeys. The female dominance order is normally quite stable, with status deriving from that of the mother. Her offspring take precedence after her, in reverse of their birth order while they are young, and she intercedes to help them. As adults, the young tend to defer to their elder siblings. Among males dominance is much less stable. The frequent arrival of new males and the departure of old ones keeps dominance in flux, as do shifting coalitions among individual males. Physical strength alone does not usually suffice to establish dominance among males, unless reinforced by social skill. Social skill is important also in establishing “friendships” with females, support within the group as a whole, and in forging alliances with other males to achieve dominant status (see sources cited above for baboons). Among gorillas dominance is quite pronounced. The silver-backed male exerts dominance over all others, but also acts as leader, protector and policeman. Females often look to the dominant male for protection against infanticide, whether by females higher in the dominance order or, much more commonly, by males trying to take over the group. Among females seniority in the group seems to exert strong influence on the dominance order. A female's offspring may also help her maintain her position (see sources cited above for gorillas). Concerning dominance among chimpanzees, Jane Goodall wrote that its benefits "seem… less significant for… males than for the males of any other primate species" (Goodall, 1986, 442). Nevertheless, her evidence shows that among males communication relating to rank is almost constant, that rank reversals almost always involve violence, and that the losers of dominance struggles sometimes disappear. Christopher Boehm (1999, 34) insists that both male and female adults “must salute any higher-ranking adult male with a submissive greeting…” (I once learned from a witness to such an event in England about a century ago that an employee who failed to tip his cap to his employer might expect a whiplash in the face). As a male chimpanzee approaches maturity, he gives high priority to establishing dominance over all the females of the group. Having secured that, he then tries usually to work his way up the male dominance order. His success in doing so will depend upon his physical strength and agility, but also on determination and ingenuity. Ingenuity can be helpful both in charging displays designed to intimidate others and especially in creating social support in the group as a whole. It can help as well in forming alliances with other males. Males who rise to a position of dominance will be deferred to in feeding and breeding, although, as observed above, usually all the adult males of a group will mate with any group female in estrus. Dominant males may also exercise a policing role over disputing subordinates. Perhaps because group members are so often dispersed, protective and leadership roles are not conspicuous. Boehm (1999, 130-131) suggests also that the inability of subordinate males to leave their group (because neighboring groups would kill them on sight) is a necessary condition for the existence of dominance hierarchies among chimpanzees. The “danger of being male is reflected in the adult sex ratio of chimpanzee populations,” as there are usually considerably less males than females (Waal, 1995). For female chimpanzees, dominance is clearly less important. As with some other female primates, it is influenced strongly by heredity. On the other hand, there seems to be a tendency for larger females to dominate smaller ones (whereas larger males are not “significantly correlated” with higher rank) (Pusey, 2005). Daughters often enjoy (hereditary) status just beneath their mothers. The chief advantage of dominance for females is priority in feeding. However, high ranking females may cannibalize the infants of subordinates. For this reason, in addition to their inferior access to food, subordinate females are generally much less successful in reproduction. Expressions of the dominant-subordinate relationship among chimpanzees require special notice. To acknowledge subordination, an individual may "present" his or her posterior as if to invite mounting, may crouch, bow, kiss, embrace, extend a hand, palm up, or the back of the wrist, touch, groom, and utter soft vocalizations. The superior may ignore these expressions of deference, or graciously touch, pat, kiss, embrace, or even groom the subordinate, as if to convey assurance of good will. Many of these behavioral patterns relating to dominance relationships, especially the bowing and kissing, are strikingly similar to those evident in many human cultures- ancient, medieval, and modern (see sources cited above for chimpanzees). Dominance among bonobos is atypical for primates. Affiliate behavior is highest between male and female adults. Next in importance are the adult female-female bonds. This contrasts with chimpanzees, where the male-male bond is paramount. Dominance relations between males and females are very often unclear, or at least flexible and subject to changing coalitions (Paoli, et al, 2005, 116). Females generally have prior access to desirable feeding sites. Males are rarely submissive to young females, but behave submissively towards a female group, as indeed females may form alliances in order to attack males who tend not to form coalitions. Unlike chimpanzees, male bonobos tend not to hunt. Large foraging parties of females can and do cooperate regularly to control the distribution of prized foods and to prevent individual males from abusing any females. Females are marginally smaller dimorphically than are chimpanzee females (Fig. 2.2). Among females, seniority in the group seems to confer status, while new arrivals suffer low rank for some time. Another salient feature of bonobos society is that mothers and sons form a lifelong bond so powerful that a mother’s help is often determinant in dominance contests amongst adult males. The male whose mother is infirm or has died suffers a significant disadvantage, although dominance orders in general appear nowhere near as important for bonobos as for other non-human primates (see sources cited above for bonobos). Clearly dominance is enormously important among nonhuman primates, including even bonobos despite their preoccupation with sex. Most of the communication within any primate group relates to dominance. Except for bonobos, males dominate females; but each sex has its own specific hierarchy as well. Males compete vigorously for status, but, particularly among baboons and chimpanzees, their success often depends on social and political skill as well as physical strength. Winners in the dominance struggle enjoy priority in feeding and breeding, but also have responsibility (at least in larger species) for leadership, protection, and the maintenance of internal order or policing. Individuals who lose dominance struggles may leave the group. Subordinates in general suffer inferior access to food and breeding. They feel less loyalty to the group and may in fact abandon it. When groups of nonhuman primates split, it is usually along dominance lines. Among females, struggles over dominance are less pronounced; heredity plays a significant role and the hierarchy is more stable than it is among males. Dominant females and their relatives take precedence over their subordinates in feeding; they may also prevent subordinates from breeding or cannibalize the infants of those of lesser rank. Larger groups exert dominance over smaller ones, even to the point of exterminating males and infants in a group inferior in numbers (see below on territorial behavior in chimpanzees). With social carnivores, dominance is also very important. Among lions its principal importance is from its absence, except for the dominance of adult males over females. Because lions do not form dominance hierarchies, intra-specific killing is far more prevalent among them than among other social carnivores (Schaller, 1972). Among hyenas, females are not only dominant over males, but, unlike lions, have a dominance order among themselves. The dominant female exercises leadership and takes precedence in feeding and in breeding (see sources cited above for hyenas). Dominance orders in wild dogs, as has traditionally been reported for most social canids, are separate for each sex, with each alpha attempting to monopolize breeding. The dominant male enjoys the usual prerogative of dominance in breeding, but also decides when and where to hunt. The dominant female usually monopolizes breeding, and the whole pack, minus a few (mostly females) who have left the group due to such dominance arrangements, helps raise her pups (Creel, et al, 1997, 298) (see sources cited above for wild dogs). With wolves, dominance is still more highly conspicuous. Subordinates, while part of the pack, are very respectful and submissive to dominant individuals. Both male and female subordinates experience harassment by the dominant alpha of their sex during breeding periods. They do not usually succeed in mating. Both males and females of subordinate status will help raise the pups of the dominant couple. While the dominant male and female are normally quite hostile to strangers, subordinates are quite friendly. Subordinate individuals may ultimately leave the group and link up with another individual of the opposite sex to start a new pack. Other subordinates will remain with or near their natal group, awaiting an opportunity to become dominant (see sources cited above for wolves). Wolves may also demonstrate resentment against extreme assertions of dominant authority. Observers in Yellowstone National Park saw subordinates, including her own daughters, unite to kill an overbearing alpha female (NY Times, July 22, 2003, D3). Among early human hunter-gatherers, dominance hierarchies were with few exceptions conspicuously absent. This striking departure from the pattern in both our fellow primates and most social carnivores demands an explanation. Clearly both chimpanzees and bonobos, our closest primate relatives, and presumably the little known common ancestor we share with them, formed dominance hierarchies. So, except for lions, did the social carnivores whose environment we shared in the formative years of our species. Why then were our hunting-gathering ancestors so different? The explanation offered by Christopher Boehm (1999, 334 ff) is that our genetic heritage in this respect has three parts, rather than merely the two characteristics long recognized: 1) the attempt to exercise dominance, or 2) the tendency to submit to being subordinate. The third aspect, no less significant, is to resent and to dislike those who exert dominance. “Where once a lion sat, there is now a pig,” was how most of the women of Vugha, Tanganyika noted the political changes from German colonisation to their traditional ways of life in the late 19th century (Iliffe, 122). It is Boehm’s contention that nomadic hunter-gatherers act (and acted) within their groups to ridicule, shame, ostracize or perhaps even murder individuals who show an inclination to set themselves above the others. Indeed Boehm cites examples of such behavior among extant hunter-gatherers on four continents (cf .Price & Feinman, 1995, 6) (see also sources cited above for hunter-gatherers). Reasonably representative of nomadic hunter-gatherers in marginal environments are the !Kung San of Richard B. Lee’s 1979 study. He found them a "fiercely egalitarian people" (244), who helped the least successful, curbed arrogance, and encouraged modesty. While no clear lines of authority could be perceived, some measure of deference was observed toward senior members of large families, male or female, native or immigrant, especially those considered "owners" of a water hole. Deference to such individuals was not automatic, however, but depended in great measure upon personal characteristics, including age. Historian John Iliffe affirms that “a ruler's authority grew with age and declined with senility” throughout traditional African societies and small states prior to their imperial conquest in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Iliffe, 1979, 25). The !Kung San, desert hunter-gatherers, were one of the relatively few groups spared this colonization. Their "leaders," Lee and others have observed, were not more privileged, wealthier, or more assertive, but quite like others of the group. To have been otherwise would have cost them their leadership and risked ostracism or worse (343 ff). The dominance phenomenon reasserts itself, however, among sedentary hunter-gatherer groups and especially among the prehistoric agricultural peoples of the Neolithic era. Among sedentary hunter-gatherers, there is little evidence that dominance struggles had become highly important, but there was increased division of labor and greater social inequality. There were, in other words, indications of incipient hierarchy. As agriculture increased production, groups tended to become larger and to compete for possession of choice sites capable of affording secure subsistence. In this they were quite like hyenas competing in groups for access to portions of an area particularly well suited to hunting. Such circumstances, tending perhaps to produce a need for charismatic authority, fostered increasing differences of status- especially for priests and warriors. Some tendency is evident also for status to become hereditary for males- not just for females as in so many of the primate groups we have considered. Hereditary status for males had become possible in hominids after the appearance of the pair-bond, but it was probably not until several eras later that Holocene-era animal husbandry practices made paternity much more evident and salient than it had been earlier. Increased division of labor brought sharper differences in economic status. This was reflected in individual burial sites. Women also suffered a marked decline in status. According to numerous studies, the transition to agriculture affected the sexes differently: “mean age at death in the…[Levant, circa 10,500-8,300 BCE] was higher for adult females compared to adult males, while in the Neolithic, it was the reverse. One interpretation given… is that with the onset of the Neolithic period, maternal mortality increased as a result of a concomitant increase in fertility” (Eshed, et al, 2004, 315). Anastasia Papathanasiou (2005) chimes in that “consistent results” from several thousand years later in Neolithic Greece reveal high child mortality, as well as increased labor loads and dominance-related violence. The “most frequent pathological conditions” typical of Neolithic Greece were 1) anemia, “2) osteoarthritis and musculoskeletal stress markers, indicative of increased physical activity and heavy workloads” and 3) “elevated prevalence of healed, depressed cranial fractures, serving as evidence of violent, nonlethal confrontations” (Papathanasiou, 377). Rick Schulting and Michael Wysocki’s recent study of some 350 skulls from southern Britain (c.4000-3200 BCE) reveals that “Early Neolithic Britons had a one in 20 chance of suffering a skull fracture at the hands of someone else and a one in 50 chance of dying from their injuries” (Rincon, 2006). Similar rates of cranial fracture were found earlier for “late prehistoric” people in Ohio (Gat, 2006, 130-131). Still more ominously, whole groups often became the victims of aliens who imposed themselves as a ruling elite, exacting tribute from or even enslaving the conquered people whom they had not massacred (Price & Brown, 1985, 5, 10, 16; Henry, 1985, 365; Knauft, 1991; Boehm, 1999; Fagan, 2001). In small groups of nomadic herders, dominance was not at all conspicuous, but it became so when larger groups had to form for military purposes. In small herding units, egalitarian practices reminiscent of hunter-gatherers prevailed. On the other hand, the leaders of expeditions for plunder, extortion, or conquest exercised authority that was charismatic in character. Even then, however, egalitarian practices remained the rule within the kin groups at the base of nomadic society (see sources cited above for nomadic herders). Dominance among modern humans, in contrast to group formation and membership, has received relatively little study. According to Taylor and Moghaddam, psychologists have been reluctant to study elite behavior and the power relationships associated with it. The political implications which could be drawn from such work, they asserted, "might jeopardize the fragile image of psychology as a science" (1987, 131). Peter Rhode searched indices of books on animal behavior, general psychology, and general psychiatry for references to hierarchy, territory, and dominance. He concluded that: “Hierarchical and territorial behavior are widespread in both animals and humans, but are neglected in textbooks of human behavior and mental problems” (Rhode, 2000). Whatever the reason, European social psychologists have also given less attention to dominance relationships than the importance of the topic would seem to warrant. Some important findings have emerged, however, from the work of psychologists who have considered dominance relationships among individuals. For example, children and adolescents tend to form dominance relationships (Strayer, 1992; Pettit, 1990; Trawick-Smith, 1992). Males generally dominate females (Melson & Dyar, 1987). Children need to learn when to assert dominance and when to submit (Weininger, 1975). Physical manifestations of dominance relationships in children and nonhuman primates are similar (Ellyson & Dovidio, 1985). Jim Sidanius and colleagues (2000) questioned roughly 7000 respondents in six nations on social dominance orientation. They concluded that “males were more anti-egalitarian than females, and that the male/female difference in social and group dominance orientation tended to be largely invariant across cultural, situational, and contextual boundaries.” Another study found that subordinates with superior qualifications are in some instances unwilling to challenge dominant individuals, because to do so would involve dangerous risks (Jackson, 1988). As with nonhuman primates, dominant individuals tend to be a major focus of attention by subordinates (Melson & Dyar, 1987). This can often contribute to the group think phenomenon- wherein groups agree to pursue identifiably bad or irrational goals with which the individual members may not necessarily agree, given serious scrutiny. In other words “rationalized conformity- an open, articulate philosophy which holds that group values are not only expedient but right and good” (Whyte, 1952, 195). Studies of elites have also reached interesting conclusions. When an elite group is closed to aspiring outsiders, the most ambitious of them "will mobilize the non-elite against the governing elite" (Taylor & Moghaddam, 1987,130). Perhaps anticipating relative deprivation theory, Joseph Lopreato (1968) found that junior executives enjoying a small taste of power and eager to increase it were far more dissatisfied with their status than were those who had no power at all. Sidanius and Pratto (1999, 44) found that “Dominant groups will tend to display higher levels of ingroup favoritism than subordinate groups will.” Thus they sow the seeds of their own eventual supplantation by more open and adaptable groups. Or as Joseph Henrich would say, “by reducing within-group variation and increasing between group variation, conformist transmission provides the raw materials for cultural group selection” (2004, 23). Generally, however, dominance relationships among groups have received much less study than they have that among individuals. John Turner did find that groups are likely to compete more aggressively than individuals in similar circumstances (Turner, 1981, 97). Hogg and Abrams found that membership in a subordinate group confers a “negative social identity” and “mobilizes individuals to attempt to remedy it” (1988, 27). Don Operario and Susan T. Fiske added that “people establish positive social identities by comparing the ingroup favorably against outgroups” (1999, 42). Bertjan Doosje and associates found that those in a low status group were more willing to affirm their membership in it, if improvement in its status was imminent or had already occurred (2002). In all the species we have considered, it also seems clear that large groups tend to dominate smaller ones, sometimes even eliminating them. An intriguing question is how dominant status among groups affects the performance of the obligations which often accompany dominance within a group: the provision of leadership, policing, and protection. Although we have found no such studies of human groups, primatologists Jeroen Stevens, et al (2005) have found that “when resources are distributed more evenly” dominant or high-rank bonobos “may peer down the hierarchy” (255). It would seem that egalitarian groups are usually more looked after and tight; whereas less equal groups appear set to face still more centrifugal forces, at least over the short term. Territoriality Territoriality is quite evident among many kinds of monkeys. When it is, the group's territory is normally a range of some size. The usual reaction of groups meeting in border areas is aversion rather than confrontation. Smaller groups are likely, as noted above, to give way to larger groups. Nevertheless border clashes do occur. The sudden appearance of a stranger is also likely to produce considerable apprehension (cf. Edward O. Wilson, 1975, 249). Recent research has indicated that macaques, like humans, have a “system for the processing of own species faces…. This specialization is achieved through experience with faces of conspecifics during development and leads to the loss of ability to process faces from other primate species” (Dufour, et al, 2006, 107). Among baboons territoriality is not conspicuous. Their usual food is of low caloric value and is normally quite widely distributed rather than concentrated. Consequently groups tend to wander rather widely and do not usually compete with others for territory. However, they do have ranges. Shirley Strum observed (1987, 80) that even in a food crisis brought on by a severe drought, a baboon group was extremely reluctant to follow an immigrant male's lead out of their territory to a food source in a new area. Generally baboon groups respect each other's core areas, and in open country often share sleeping areas, usually cliffs or rock outcroppings, quite amicably (see sources cited above for baboons). With gorillas territoriality does not seem important, probably because, as with baboons, their usual foods are so widely scattered and of such limited food value. Fighting among males usually relates not to territory, but to competition over females. Females do show preference for a silverback capable of defending them and their offspring against infanticidal male intruders (see sources cited above for gorillas). Among chimpanzee groups, however, territoriality is very strong. Jane Goodall (1986) in her chapter on “Territoriality” affirmed that chimpanzees seem to have an inherent aversion to strangers, that their territories are usually large, and their borders not too clearly defined. Nevertheless she and her associates observed that patrols went out every few days to check their borders. Such patrols always showed a high level of anxiety in border areas. If they encountered a neighboring group of about equal size, each group would threaten the other aggressively and then retreat. If one group were larger, it would pursue individuals of the smaller group into its territory. The aggressors would then fatally maul individuals they captured. The victors might then incorporate some of their neighbor's territory and its females, after cannibalizing infant offspring, so that their mothers would become sexually receptive sooner (see sources cited above for chimpanzees). Although bonobos in the wild have been much less closely observed than chimpanzees, territorial behavior appears to generally consist of "vocal contests" and avoidance of confrontation (San Diego Zoo). Sexual activity, again, appears to be “the bonobo's answer to avoiding conflict… anything, not just food, that arouses the interest of more than one bonobo at a time tends to result in sexual contact” (Waal, 1995). Bonobos very rarely, if ever, bother to hunt vertebrates and usually experience no problems with their food supply of fruits and plants. Aggressive displays, territorial or otherwise, are much milder than with chimpanzees. Territoriality thus varies considerably among nonhuman primates. It seems relatively weak in most monkeys, baboons, gorillas, and even bonobos- probably because their feeding pattern is to forage for material of relatively low food value which is widely dispersed. Chimpanzee groups, on the other hand, are strongly territorial. The very reason for the existence of the male-bonded groups seems to be to protect and, if possible, expand the group's territory and thus both its preferred food supply and its access to females. Chimpanzees, by no means coincidentally, are the only primate groups in addition to ours which engages in hunting other mammals. Among social carnivores, territorial behavior tends to be stronger, but also varies considerably. Lion prides are highly territorial. A principal function of the resident males in a pride is to mark off and protect the pride’s territory against intruders. Females assist, some more eagerly than others, in this role of protecting the pride’s territory (see sources cited above for lions). In hyenas, the spotted hyena in particular, territorial behavior is especially intriguing. When prey is widely dispersed, groups of spotted hyenas tend to break up and small groups or even individuals forage independently over a wide area. However, when prey is locally concentrated in limited areas of particularly lush grassland, groups become tightly organized and highly territorial. Rival groups mark their territorial borders as a group, defend their territory against intrusion, and generally avoid significant intrusion into the territory of others. Indeed groups have been seen to give up pursuit of prey at their border, even to surrender prey killed outside their borders when the "owners" of the territory show up. Jane Goodall observed, however, that hyenas confident of superior numbers manifest no inhibitions whatsoever about intruding aggressively into the territory of another group (Goodall, 1986, 526). Individuals however, especially males and juveniles, often traverse territorial borders with impunity (see sources cited above for hyenas). Packs of wild dogs appear generally to be nomadic rather than territorial, except in the den area when there are pups (see sources cited above for wild dogs). Wolf packs, like lions, are quite territorial. They mark borders and will defend a core area. Their territories are so large, however, that it is usually not feasible to defend them against peripheral intrusions. In following prey, especially migratory prey, they change their territories frequently. Such border shifts and the departure of maturing individuals from the territory of their native pack make territorial intrusions a leading cause of mortality. Territorial aggression is most likely to occur with males, “however competitive aggression occurred more often with females… food deprivation increases occurrences of competitive aggression”, although it also decreases incidents of territorial aggression as well (Stiles, 2006, 4) (see sources cited above for wolves). Territoriality was minimal among the desert !Kung San. Lee observed that neighboring groups experienced "surprisingly little friction" (350). Indeed when drought dried up most water holes, a number of !Kung San groups would camp together where one water hole was still producing. Each group returned to its territory when rainfall renewed the water holes. Obviously the !Kung San did have territorial ranges, but the borders were quite indistinct and neighbors who asked politely were welcome to share a group's resources. This was done with the expectation that the favor would be returned in the future. In an arid area where rainfall was quite spotty as well as sparse, territoriality, Lee observed (360 ff), was not the best strategy. Rather the !Kung San maximized population density by practicing "reciprocal access to resources." In very dry weather their groups congregated at the few remaining water holes, and dispersed when rainfall renewed flow (337, 350 ff). In addition to maximizing population, such policies also minimized bloodshed. Challengers to this idyllic and consensual picture of life among hunter-gatherers have found that elsewhere (with higher rainfall and population densities) such groups frequently engage in warfare, sometimes involving territorial disputes (Boehm, 1999, 81; Gat, 2006). Among complex hunter-gatherers, the importance of territory became much greater. As human groups became larger and heavily dependent upon exclusive possession of a particular territory for a secure subsistence, they began to mark territorial borders and to defend them against intrusion. As mentioned earlier, the first clear evidence of mass victims of intraspecies violence, however, only dates back to around 14 kya. After the widespread development of agriculture, territoriality became still more intense, especially in those limited areas well suited to growing crops. Border conflicts multiplied exponentially. Preliterate communities dug ditches or built walls, some of them massive in size, to protect their land and its people from plunder or, still worse, from conquest by outsiders who coveted at a minimum their stored foods, but often also their territory and labor (see sources cited above for early agriculturalists). Among nomadic herders, territoriality was usually less intense. Herding groups often had only vaguely defined territorial ranges within which, however, they often had well-established seasonal patterns of migration. There could be violence if flagrant territorial intrusions occurred, but warfare among nomadic herders generally took the form of raids upon another group's livestock. Its territory was not usually at issue. In their attempts to conquer and impose their rule on sedentary farmers, however, nomadic herders showed great interest in territory (see sources cited above for nomadic herders). Territoriality has received extensive study with reference to fish, amphibians, reptiles, insects, birds, and nonhuman mammals, but in relation to the behavior of human behavior "serious scholarship has only skirted its perimeters" (Sack, 1986, 1; cf Taylor, 1988). Even European social psychologists, who have done much work on the behavior of human groups, have done little on territoriality. Those researchers who have investigated territoriality, notably environmental psychologists, have tended to do so with reference to individuals and small groups. They have concluded that territory is psychologically important, especially so for mental patients and the elderly (Kinney, 1987; Altman, 1975). Geographer Torsten Malmberg in a wide-ranging book on Human Territoriality (1980) insisted that it had a basis in instinct (305-306), that it was evident early in children, and especially strong in mentally retarded boys (308). Recent international studies of college students, however, have shown that although young men “tended to exhibit more nonsharing behavior”, they also exhibited “less personalization of space than women” (Kaya & Weber, 2003). Perhaps clarifying the above contradiction, Dolapo Amole concludes that women “make more use of territorial strategies”, whereas males appear to "use withdrawal strategies more often” (Amole, 2005). Cooperation and Sharing Cooperation is more easily observable among monkeys than is sharing. Group members cooperate in conflicts with rival groups, but in the wild they do not often share food among adult members of a group. The plant foods which are their usual fare are typically quite dispersed, often of bite size or smaller, and most importantly of low caloric value. Thus sharing is not so clearly practical for them as it is for social carnivores. In the wild others of the group will usually not take on the nearly impossible burden of trying to provide food for an adult unable to provide for itself. Monkeys do, however, manifest concern for other group members. They give warning, even at considerable risk to the individual doing the warning, of the approach of predators or other dangers. They show care also in mutual grooming, although that practice may relate to expressions of dominance relationships as well as caring (Bernstein & Smith, 1979; Dunbar, 1988; Mitchell, 1979; Poirier, 1972; Gouzoules & Gouzoules, 1987; Cheney & Seyfarth,1981, 1982, 1990; Seyfarth & Cheney, 2003; Lawes & Henzi, 1995; Boinski & Campbell, 1995; VanSchaik, 1992; Gust, 1995; Kuester, 1994; Schuster, 1992; Takata, 1994; Bernstein, 1993; Lyons, 1994). Among baboons behavior relating to cooperation and sharing is similar to that among monkeys. The most notable difference is in the protective role which individual males may take toward female “friends” (Smuts, 1985) and their offspring (Kummer, 1968, 1995; Ransom, 1981; Smuts, 1985, 1987; Strum ,1987; Stammbach, 1987; Melnick & Pearl, 1987; Pusey & Packer, 1987; Smith, 1992; Bercovitch, 1995). Cooperation and sharing among gorillas, as with baboons and other monkeys, is minimal and for the same reasons. They have even less need to cooperate for defense (Fossey, 1983; Bourne, 1975; Dixson, 1981; Maple, 1982; Schaller, 1963; Cheney, 1987; Stewart & Harcourt, 1987; Sicotte, 1993; Watts, 1994; Robinson, 2001). Chimpanzees cooperate and share more than do other nonhuman primates. Chimpanzees cooperate, for example, in patrolling their borders as well as in intergroup conflicts. They sometimes cooperate in hunting. Males who have captured and are eating an animal will usually share the carcass with others when begged to do so. Males coming upon a loaded fruit tree, as noted above, will summon others of the group by vocalizing loudly. Females in the same circumstance, perhaps because of their subordinate status which would result in males taking the dominant‘s portion, typically share the find only within the discovering group, usually an adult female and her offspring. Wild chimpanzees, like other nonhuman primates, will not generally attempt to feed an adult individual or even a weaned infant unable to feed itself. Captive chimpanzees, however, will sometimes share food (Goodall, 1986; Ghiglieri, 1988; Waal, 1982, 1987, 1989, 1994, 1996, 2001a, 2001b; Wall & Tyack, 2003; Nishida, 1987, 1990a, 1990b, 1990c; Walters & Seyfarth, 1987; Hasegawa, 1990; Takahata, 1990; Uehara, 1994; Chapman & Wrangham, 1993; Clark, 1993; Wrangham, et al., 1994; Mitani, et al., 2000). Male bonobos tend to be less like chimpanzees and more like gorillas and monkeys in terms of cooperation. Females however (as noted above), regularly cooperate in forming their unusually large and flexible foraging groups and coalitions, the basis of their distinctly un-primate-like power over males (Parish, 1996, 61). Bonobos, moreover, generally share both meat and frugivorous food more often than do chimpanzees, who only share meat. Again, female-female sharing tends to be the norm with bonobos. In fact, great ape behaviorist Craig Stanford has noted that “hunting by bonobos may be less frequent than hunting by chimpanzees because female bonobos have greater control of food resources” (Stanford, 1998, 409). As they are hunters, cooperation and sharing are much more significant in social carnivores. Most adult members of a lion pride will take part, some with more enthusiasm than others, in defending the pride’s territory. Females of a pride sometimes hunt cooperatively. They also share their prey with other pride members, usually very grudgingly. Mothers may share nursing duty as well (Schaller, 1972; Packer & Pusey, 1982; Packer, 1990; Pusey & Packer, 1994; Kruuk, 2003). Cooperation and sharing among hyenas is much the same, with group cooperation in hunting even more prevalent than among lions. Hyenas also cooperate closely, as observed above, in marking and defending territorial borders. Feeding on prey is aggressively competitive, but some sharing may occur (Kruuk, 1972, 2003; Frank, 1986; Mills, 1990; Henschel & Skinner, 1991; Jenks, 1995). Wild dogs cooperate and share much as wolves do. They cooperate closely during the hunt and, like wolves, will regurgitate food for the pups and for the ill or disabled of the group which were unable to take part in the hunt (Lawick-Goodall, 1971; Sheldon, 1992; Creel, 1995). Among wolves both cooperation and sharing are still more pronounced. They cooperate quite closely in both hunting and in their frequent conflicts with neighboring groups. Although the feeding order is set by dominance and there may be conflict at a crowded kill site, at the den hunters will regurgitate food not only for pups, but also for adult members of the group unable to participate (Mech, 1970, 1998; Klinghammer, 1979; Harrington & Paquet, 1982; Fox, 1975, 1978; Hall & Sharp, 1978; Altmann, 1987; Hoof, 1987; McDonald, 1987; Savage, 1996). Cooperation and sharing were outstanding features of the humans who lived as hunter-gatherers in the tens of thousands of years in which some of our ancestors moved out of Africa and spread over nearly all the earth. This record, we should remember, affords a sharp contrast to our closest living relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos, who cooperate and share less and have remained confined geographically to their original habitat in tropical Africa. Hunting herbivores much larger than they were certainly required male hunter-gatherers to cooperate closely. Surviving groups of hunter-gatherers still do so. Meat, the highly valued product of hunting, had to be shared among group members. Indeed reluctance to share almost anything of great value was highly reprehensible behavior which was likely, as observed above, to bring on punishments ranging from collective ridicule to community- sanctioned murder. Decision-making for the group also involved sharing of authority, in that decisions were usually made by consensus (see sources cited above for hunter-gatherers). While conspicuous among hunter-gatherers and probably accountable in some measure for their evolutionary success, cooperation and sharing seem to have diminished in importance among sedentary farmers. In such groups, cooperation was still the rule in matters of group defense and for public works. However, specialization of labor and individual/family ownership created differences in status which became in some ways similar to the dominance hierarchies of nonhuman primates. As with the primates, such differences in status tended to reduce loyalty to the group among those of lower status, and lowered their rate of reproductive success as well. Recent DNA studies have found that a typical woman through human history was about twice as likely to reproduce as was a typical man, by a ratio of approximately 80 percent to 40 percent (Tierney, 2007). Those of higher status, especially the priests and warriors classes, also tended to accumulate more and more material benefits with agriculture, in addition to great authority. Nomadic herders cooperated in tending and defending their livestock, despite the fact that ownership of the animals was not communal, but with individual families. They often cooperated also in offensive alliances, from raiding other nomadic groups for livestock, to attacking sedentary farmers for plunder, “protection” fees, or for subjugation and acquisition of coveted territory (see sources cited above for complex hunter-gatherers, early farmers, and nomadic herders). In modern human society, cooperation is obviously essential, but sharing outside of the family, whether nuclear or extended, is less widespread. It is also the subject of academic dispute. Evolutionary psychologists (the former sociobiologists) have preferred generally to focus on what they call “altruistic behavior” rather than sharing. They argued for some time that, from an evolutionary standpoint, altruism is counter-productive, unless limited to genetically related individuals or to those confident of reciprocity (Hamilton, 1964; Trivers, 1971; Dawkins, 1976, 1989; Alexander, 1987; Axelrod, 1987). Perhaps they had not fully considered human norms of reciprocity and social learning, or human sexual selection. Social psychologist C. Daniel Batson’s “empathy-altruism hypothesis” stipulates that, when we feel empathy for a person, we will attempt to help them purely for altruistic reasons (regardless of reward): Whereas if we do not feel salient empathy for a person, only then do social exchange concerns (cost: benefit analysis) come into play. Is there anyone watching? Do the potential social rewards of helping outweigh the costs? (Aronson, Wilson, & Akert, 2005, 362-63). The behavioural contrast between humans and animals is perhaps sharpest on this matter. There is “little evidence so far that individual reputation building affects cooperation in animals, which contrasts strongly in what we find in humans” (Fehr & Fischbacher, 2003, 785). For men, some of the presumed social rewards for altruistic behavior appear to include being “perceived as more physically attractive, more sexually attractive, more socially desirable, and more desirable as a date” (Jensen-Campbell, et al, 1995, 437). Indeed, in modern US university settings at least, dominance appears “to have no effect on the attractiveness of men who were low in agreeableness. For men who were high in agreeableness, however, dominance did increase subjective physical attractiveness, sexual attractiveness, dating desirability, general social desirability, and perceived wealth later in life” (438). The team found “no evidence that female dominance affected attraction” from men (438). Social psychologists have found abundant evidence that altruistic behavior is not merely reserved for those perceived to be of close genetic similarity (as is typically the case with almost all social animals), or even reserved for situations of expected reciprocity. Young children, for example, spontaneously show helping and giving behavior, as well as empathic distress, towards unrelated peers (Grusek, 1991; Kakavoulis, 1998). So powerful is human sociality that anyone, given the right conditions, can feel powerful urges of empathy and compassion. Even rhesus monkeys prefer starving themselves for several days to pulling a chain for food that would also deliver an electric shock to a companion (Wade, 2007). Those with high levels of testosterone, however, are less likely to manifest prosocial behavior, unless they are of high status (Dobbs & Morris, 1990). Those seen as leaders were more prosocial than others (Ginsburg & Miller, 1981). David Barash, commenting on such differing opinions, observed that while nature seemingly “abhors true altruism. Society, on the other hand, adores it” (Barash, 2003). Indeed, few human institutions have been as euphoric through the ages as the generous feast. Closely related to the debate on altruism is that over the concept of group selection- an idea repudiated in the 1960s that is now experiencing a revival, sparked in part by Sober and Wilson’s Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior (1998), which pointed out that groups as well as individuals compete, and that as such altruists tend to make better parents than egoists. Another study by Robert Boyd, et. al (2003) for the National Academy of Sciences argues that altruistic punishment (the punishment of non-cooperators) helped the evolution of cooperation, primarily by reinforcing altruistic cooperation (where individuals that cooperate pay a cost; but the society as a whole benefits). Or in the words of anthropologist Joan Silk, “Humans are the most cooperative species on the planet, and the most punitive. This is no coincidence” (Silk, 2007, 13537). As Urs Fischacher, et al. explains, altruistic punishment has been a decisive force in the evolution of human cooperation. Using brain scans, his team found that “Effective punishment, as compared with symbolic punishment, activated the dorsal striatum, which has been implicated in the processing of rewards that accrue as a result of goal-directed actions. Moreover, subjects with stronger activations in the dorsal striatum were willing to incur greater costs in order to punish…. people derive satisfaction from punishing norm violators” (Fischbacher, et al, 2004, 1254). In a paleolithic family environment, or anywhere else "where altruistic cooperators and punishers are frequent, within-group selection against altruistic punishers is very weak", simply "because noncooperation rarely occurs and, hence, few punishment costs have to be born by the altruistic punishers (a logic first pointed out by Henrich and Boyd 2001). They show that... in the absence of altruistic punishment, within-group selection against altruistic cooperation is always strong. Thus, cultural group selection cannot sustain altruistic cooperation without altruistic punishment" (Hammerstein, 2003, 77). Social psychologists established long ago that individuals attach great importance to group membership. We see it as important to our own well-being or even survival. Consequently we are likely to try to maintain or to enhance our status within the primary or most important group(s) and above all to avoid being expelled. Furthermore, the evidence indicates clearly that groups of primates, whether human or nonhuman, nearly all compete, that stronger groups do at times take resources or territory from weaker groups, and may even at times attempt to exterminate (not just subjugate) smaller ones. Such competition among groups could hardly fail to influence the survival and reproductive success of group members. It would seem also to have afforded an advantage to those groups in which many members were genetically inclined to avoid selfish behavior, to conform to group expectations, and to help others in their group unselfishly (see inter alia Sober & Wilson, 1998; Wilson, 2003; Axelrod, 1984; Sahlins, 1976; Dawkins, 1976, 1989; Scott, 1989; Buck & Ginsburg, 1991; Sesardic, 1999; Nichols, 2001; Bahr & Bahr, 2001; Zahavi, 2000; Pergini & Galluci, 2001; De Cremer & van Lange, 2001; Krueger, et al, 2001; Kruger, 2001; Kelly & Dunbar, 2001; Pakaslahti & Keltikangas-Jaervinen, 2001; Boyd, 2003). Conclusions on Behavioral Predispositions In our search for greater understanding of human behavior as it relates to the creation of nationalities, we have now looked at the behavior of a number of animals: 1) nonhuman primates with whom we share nearly all of our genetic makeup; 2) social carnivores whose environment and dietary habits we shared in the long period in which evolutionary adaptations made us significantly different from those closest primate relatives; 3) both egalitarian hunter-gatherers and 4) the hierarchical agriculturalists who succeeded them; and finally 5) modern humans as revealed in the findings of social scientists. What insights has this inquiry afforded as to why humans form nationality groups? Group membership is clearly of enormous importance for all the species we have considered. Individuals in groups do much better in terms of survival and reproduction than do those without group ties. One sex or the other generally remains in its native group and gives great loyalty to it. Those who leave their native group, whether to avoid inbreeding or because their place in the group’s dominance hierarchy is unacceptable, make great effort to win acceptance into another group. In all the species considered, naturalization into another group is often difficult and time-consuming, but usually successful. Naturalized members then give great loyalty to their new group, even when it is in conflict with their native group. The importance of group membership to humans in particular is evident in many ways. For example, members usually conform to group expectations. We often sacrifice to serve group interests. We punish deviant or antisocial behavior by others, especially if it threatens group unity or even survival. We quite often exaggerate the virtues of our own group and the vices of others. Worth noting also is that male-bonding has been fundamental to human groups. As with chimpanzees and (to a lesser extent) bonobos, males tended to stay in their native group while females often emigrate, as in the biblical story of Ruth. Thus it is that in human groups kinship is of fundamental importance, but more so for males than for females. However, it is also clear that as human groups grew larger following the advent of agriculture, exogamy and other transfers of members between territorial groups fell sharply. The probable explanation is that groups were then large enough so that inbreeding could easily be avoided without leaving the group. Furthermore, intergroup relations had by then become poisoned by reciprocal fear of attack for plunder of stored wealth, for tribute, “protection,” or territorial conquest. The dominance phenomenon is rather more complicated. Except for lions, all the nonhuman groups considered establish dominance hierarchies that are central to their social organization. Dominance hierarchies tend generally to establish priority in feeding, in choice of location, and in breeding. In many cases they also impose upon the dominant individual heavy responsibilities for protection, internal policing, and leadership. In groups of human hunter-gatherers, on the other hand, pervasive egalitarianism replaced the traditional primate dominance hierarchy. Instead of a dominance hierarchy, such groups show essentially consensual authority with minimum guidance from respected elders and equal sharing of meat and some other properties. Christopher Boehm (1999) explains this by suggesting that our genetic heritage includes aversion to being dominated, as well as the inclination to seek dominance or accept subordination. He adds that in hunter-gatherers, the group as a whole had assumed dominance and coerced individuals to conform to an egalitarian standard. The need for protecting the group and policing its members also appear to be communal responsibilities in these smaller groups. With the transitions to sedentary foraging and agriculture, however, dominance hierarchies return to human groups. Priests and warriors in particular assumed privileged, sometimes even hereditary status. Our own suggestion to explain, at least in part, the reappearance of the hierarchical phenomenon is that prolonged exposure to conditions of extreme danger leads people to lessen their identification with large groups. Instead they manifest individual dependence upon a charismatic leader or institution. Early agriculturists confronted such conditions often as they competed for possession of choice locations and confronted natural disasters and frequent famines. Territoriality seems evident to some degree in all the species considered (least so perhaps in gorillas). It seems to arise from competition among groups, especially for secure access to the means of subsistence. Chimpanzees seem also to seek it for greater reproductive opportunities. The role of cooperation and sharing is controversial. Among nonhuman primates, both are evident, but at a rather low level relative to individual competition for dominant status. Both cooperation and sharing tend to be more prominent in the behavior of social carnivores. Human adaptation to the savannah environment and meat-eating, while growing significantly different genetically from our closest primate relatives, clearly imparted within our species a greater inclination to cooperate and share than is typical of nonhuman primates. Egalitarian cooperation and sharing were extraordinarily prominent among our hunting and gathering ancestors. Those qualities, along with adaptability, served hunter-gatherers well, as perhaps only a few thousand moved out of Africa to cover nearly all the earth. With the advent of agriculture, however, dominance hierarchies more like those among other primates returned. For many millennia competition tended to intensify, both within and between increasingly endogamous and hierarchical groups. The role of group selection and altruism in the evolution of human behavior is still controversial. Group membership is so important to most humans that it impels them to do whatever the group expects of them, and to avoid actions which might risk expulsion or still more extreme sanction. Rescuing or aiding a fellow group member in distress would serve both of these purposes. Refusing to aid a group member in distress would presumably weaken group solidarity and perhaps eventually put one’s own membership at risk. This suggests that "interdependence of fate" (Lewin, 1948, 184) may help explain not only how the basic ties of group membership can arise- with or without the existence of ethnic ties- but also how cooperation and sharing became widespread within human groups. After all, within a band there is no place to hide from one’s reputation. Collectively these findings serve to recall the observation of William James (1890, II, 409): "As with all gregarious animals, 'two souls,' as Faust says, ' dwell within his breast,' the one of sociability and helpfulness, the other of jealousy and antagonism to his mates." To recast his point in the terms employed in this study, human beings seem naturally inclined to be helpful and cooperative toward members of their group. On the other hand, they often compete avidly with other members of the group to attain and maintain the highest position they can reach within it. Frans de Waal made fascinating observations on similar behavior among chimpanzees in Chimpanzee Politics (1982) and in Peacemaking among Primates (1989). Fig. 2:2 Summary Behavioral Predispositions of Primates and Social Carnivores ' GF & Membership Dominance Territoriality Cooperation Sharing ' (and dimorphism3) Modern ethnic, civic, CHA/CHD understudied; understudied; high; high/complex; * (76-88%) kids/group think w/populat. density normative institutional Herders exogamy; patriarchal only in large, vaguely defined high; often high; * (76-88%) charism. groups war/raids meat/land Farmers endogamy; patriarchal hierarchical; vigilantly defined high; occasionally * (76-88%) priests&warriors normative high; fests H-G’ers exogamy/egalitarian absent/resented low (populat. very high; very high; * (80-85%) density) constant constant lions sisters-bond; w/ low or absent vigilant; high hunting; * dom. or nomad males (73-80%) maintained nursing wolves alpha pair conspicuous, vigilant; very high hunting; * (80-82%) but resented maintained raising pups wilddogs male-bonded; somewhat conspic; only dens high hunting; * alpha pair (103-107%) female resented raising pups hyenas sisters-bonded female hierarchy; flexi-vigilant high only hunting * fusion/fission (120-125%) fluid and defense bonobos male&female-bonded; female groups; weak n/a female female * large groups; stable (77%) seniority groups groups chimps male-bonded; small political, male; strong; irreg. high: male male; * group loyalty (78-79%) some seniority maintained groups politicized gorillas harems or only-male pronounced; inconspicuous inconspicuous minimal * (50%) male seniority or absent or absent baboons female-bonded; fluid unstable; inconspicuous in defense; minimal * (less than 50%) maternal or ‘friends’ monkeys4 female-bonded; often-disputed; apprehensive; in defense minimal * (63-100%) maternal larger group of group ' GF & Membership Dominance Territoriality Cooperation Sharing ' (and dimorphism3) CONCLUSION What ought we to conclude as to why we form nationalities? Five conclusions seem paramount. First, individuals of the human species choose to live in groups because they are genetically programmed to feel secure when they have strong ties to a group, and to experience nearly intolerable insecurity when they do not. The family is of course the group which provides such security at the most basic emotional level. Second, human beings also feel a need for physical security beyond that which the family can provide. People seem to be highly conscious that members of small groups tend not only to suffer low status compared to those in large ones, but also that a small group is likely to be dominated by a larger one and perhaps even exist at its sufferance. Consequently, individuals crave security against dispossession, enslavement, or murder by members of a rival group. Protection against such dangers and other threats requires membership in a group that is larger or presumably stronger than its perceived rivals. Third, individuals tend to behave in ways that meet the expectations or serve the interests of the group upon which they depend. Doing so solidifies or enhances their status within the group. Failing to do so risks punishment, loss of status, and possibly expulsion or even execution. Fourth, when human groups become aware that they have differing social identities, they tend to compete for superior status and, when circumstances warrant, for material advantage. The status rivalry arises because we are all programmed genetically to seek dominant status for the group with which we identify whenever it comes into contact with another group whose social identity is perceived as different. Establishing such group dominance not only enhances our status as individuals, but also improves the prospect that when real conflicts of interest do arise, that our group will prevail. Fifth, a territorial group recognizing interests of great urgency common to its members will seek sovereign power- the chief hallmark of a nations in the territorially-defined sense, and the usual aspiration of nations in the ethnically-defined sense. Group members in such circumstances seek sovereignty both because it enhances group status, and because it greatly facilitates the optimal utilization of the group’s resources to serve their interests. On what basis do people form new nationalities? Those of the ethnic variety form when groups sharing ancestry, language, religion, other cultural features or some combination of these, grow increasingly aware of an important rivalry with one or more groups that have different characteristics. Nationalities of the civic variety form in either of two ways. The first is secession. Diverse peoples previously part of one group or state may become dissatisfied and seek separation. One possible explanation is that noted by Edward Shils (1960): distant authority tends to be perceived as alien authority, regardless of ethnicity. A more general observation is that based on Sumner's distinction between ingroups and outgroups. Any categorization of a previously unified group of people into distinctive subgroups tends to produce bias in favor of the ingroup and against the outgroup. Categorization may also produce the labelling phenomenon- groups taking on an identity attributed to them. In so doing they become motivated to do whatever is required to raise the status and power of the group with which they have become identified. Distinctions between or among such groups may easily escalate into a status rivalry, potentially a dominance contest. If a conflict of material interests is also present, the rivalry intensifies, and the demand for sovereign authority in any subgroup not possessing it increases. The second possible pattern for the formation of new nationalities of the civic variety is the fusion of people who had previously belonged to different groups. As Sherif showed, the appearance of a goal of extraordinary importance achievable only- or perhaps only most quickly and effectively- through cooperation of previously hostile groups can blend them into a new group. Similarly the labelling phenomenon, the mere attribution of identity by outsiders, can create a "social identity" among people never previously conscious of any basis for unity, and perhaps even previously split into very hostile groups. Another observation on the formation of nationalities in the modern world concerns which of the many groups with which people identify they choose to make highest or sovereign- that is with exclusive right to exercise supreme political authority over a territory, or group of people. Should the basis of sovereignty be ancestry, language, or religion; should it be exercised by the household, the neighborhood, the city or town, the state or province, the region, an existing ethnic or civic "nation," the continent, or the planet? On what basis do people decide? The paramount concern in answering that question appears to be which group is perceived as having the most important common interest or the most important rivalry with outsiders. That group will be the one chosen to exercise sovereign power, so that it can achieve optimal mobilization of resources to meet the perceived challenge. Fig. 2:3: Modern Human Brain The Seat of Social Intelligence? “Unlike other animals, human cooperation varies in both scale and behavioral domains across social groups… many social groups inhabit the same physical environment and possess the same technology, but cooperate to differing degrees and in different domains. Standard evolutionary approaches struggle with these uniquely human observations- in other animals, cooperation and sociality do not vary much from group to group within a species" species.” - Joseph Henrich, 2004 (30) Finally we need revisit the human brain. The amygdala, as Jorge L. Armony observed, is “a critical component of the neural system involved in learning about stimuli that signal threat.” That neural system, he added, “has remained essentially unchanged throughout evolution” (2002). Because the amygdala responds to signs of danger more rapidly and often powerfully than does the more rational brain, there does appear to be reason to suspect that our impulsive behavior upon encountering members of another group may resemble that of other animals. This calls to mind Edward O. Wilson’s observation that: “The strongest evoker of aggressive response in animals is the sight of a stranger, especially a territorial intruder.” Thus we need to consider the possibility that this primitive portion of the brain may predispose us to react with fear or even hostility to those who are members of a group other than our own. Furthermore this impulse from the amygdala may produce action before the rational brain has had time even to consider the matter. The more basic point about the human brain, however, must be that, to a much greater extent than have those of either nonhuman primates or social carnivores, our brains have programmed us to be adaptive. We alone among the groups considered here have adapted to virtually all of the world’s differing climatic conditions. Through adaptation, and sometimes very quickly, to environments ranging from rainforest to desert, from tropic heat to Arctic cold, we have proved ourselves capable of altering our behavior when survival requires change. The question still open is can we change our behavior relating to the formation and the competitive relationship of nationalities sufficiently (and in time) to avert disaster for our species and planet. Creative answers to the unprecedented challenges now facing humanity will likely come from a region of the brain far removed from the reptilian amygdala. It has long been known that the human anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is home to an unusual cell type, giant spindle-shaped neurons. Over the past decade, neuroscientist John Allman and others have discovered that the ACC, “a hub from which many circuits branch out- is almost always active when human subjects are experiencing emotions or need to think about things that are difficult.” These relatively enormous spindle cells (also called von Economo neurons) “collect information from one region of the brain and send it on to other regions. They function like air traffic controllers for emotions. They seem to lie at the heart of the human social emotion circuitry, including a moral sense” of what is socially appropriate (Blakeslee, 2003). Anthropologist Mark Flinn adds that spindle cells “potentially link distinct components of the brain, providing a mechanism for monitoring performance and rewarding success via the rich dopaminergic cells of the ACC (Allman, Hakeem, Erwin, Nimchinsky, & Hof, 2001). These and other structures provide the neurobiological bases for the remarkable human abilities of self-awareness, theory of mind, empathy, and consciousness (Adolphs, 2003; Seigal & Varley, 2002)” (Flinn, 2004, 80). The ACC is also “implicated in volition, the experience of intense drive states, self-awareness and control, the discrimination of information from conflicting cues, focused problem solving, and error recognition” and relays information about these functions to other parts of the brain (Allman, 2002, 341). "’The main thing [spindle cells] do is to adjust your behaviour in a rapid real-time interaction in a complex social environment’" (Phillips, 2004). Thought to be unique to humans, whales, and great apes, spindle cells are embryonic in chimpanzees, but must migrate into the ACC, beginning several months after birth in humans (Allman, 341), and are not fully in place and functional until age three or four. Adult humans have about 15,000 spindle cells in the Brodmann’s 10 area of the brain; Bonobos 3,000; Chimpanzees 2,150; Gorillas 2,000; Orangutans 1,900 (Allman, 2002, 338). In the words of neuroscientist Roger Bingham, we are now able to “see how resentment, a sense of fair play, righteous anger and other complex social emotions come into our everyday lives” (Phillips, 2004). Perhaps spindle cells also provide an answer as to why humans have had remarkably different cultures while other species have not; or as Liah Greenfeld might say “the empirical generalization that humanity constitutes a reality sui generis, distinguished from the rest of the animal species by the symbolic… transmission of its ways of life across generations” (Greenfeld, 2004, 1). “Human history, in distinction to the development of other animal species, is… subject to the regularities of cultural, rather than biological evolution…” (2). Cultural evolution means group selection, as opposed to individual, and requires some degree of group cohesion and distinctiveness for lasting success. How have groups achieved this necessary cohesion? According to Henrich (2004), intergenerational transfers of specific cultural knowledge, or conformist transmissions, provide an “important reason why people in the same social group tend to believe the same things and why these beliefs persist over long periods. Without a conformist component to create ‘cultural clumps’, social learning models predict (incorrectly) that populations should be a smear of ideas, beliefs, values and behaviors…” (23). Conformist transmissions and observational learning (see chapter 3) have helped groups of people to focus their minds and creativity on solving the social problems of their day- be they predominantly environmental or political in nature. We are genetically programmed to conform to (and hence ourselves propagate) group norms over the course of our lives, as well as to seek out more efficacious and pleasant ways of doing things. The combination of intergenerational ‘conformist transmissions’ and spindle cells’ regulation of their expression would seem to indicate that our ancestors, as far back as the complex hunter-gatherer societies in the late Paleolithic (c.25-10 kya), were forming proto-national groups of distinctive identity and culture. These groups- to the extent that they were populous enough to be ‘imaginary communities’ (with corresponding imagined ‘others’ and foreigners) and trophically insecure- were almost certainly rivalrous, whether or not such rivalries turned to organized violence, as is first evidenced from approximately 14 kya. We create nationalities, and the requisite national rivalries to keep them going, because they work. They have worked to provide us with ever-larger and more complex forms of economic interdependence, and the gradual extension of societal trust and decency that accompany it- essentially a great process of turning strangers into (de facto) extended family and friends. These are men and women of the cultural nation- those whose brothers, sisters, and resultant social networks (imaginary or otherwise), are countless. Nations and national rivalries had grown so large and powerful by the 20th century, however, that they are now increasingly being called into question. National rivalries underlie and aggravate all the major terrestrial threats to human well-being and the survival of species on earth, perhaps even our own. War, economic breakdown, environmental devastation, terrorism, and climatic crises- each is a threat made greater by rival nations seeking a competitive advantage. We need to adapt now to the circumstances that have made competing national groups (and multi-national corporate organizations often competing in the name of national groups) such a threat to life on this planet. Improving our understanding of how competing nationalities originate might help achieve that goal. ' text copyright 2008 Philip L. White and Michael L. White |

| Ch.2-Sect.A- Evolution & Group Formation pp. 51-83 (33) Ch.2-Sect.B- Dominance, Territoriality,Cooperation/Sharing, and Conclusions pp. 83-104 (21) Ch.2-Sect.C- References pp. 104-133 (29) Chapter 1 Chapter 3 Return to Index |

Ch.2-Sect.A- Evolution & Group Formation pp. 51-83 (33) Ch.2-Sect.B- Dominance, Territoriality,Cooperation/Sharing, and Conclusions pp. 83-104 (21) Chapter 1 Chapter 3 Return to Index |

Empathy Terms

1.Emotional contagion- Similar emotion is

aroused in the subject as a direct result of

perceiving the emotion of the object.

Synonyms: Vicarious emotion, emotional transfer

Sympathy- Subject feels "sorry for" the object

as a result of perceiving the distress of the

object. 2. Identification

Empathy- Subject has a similar emotional

state to an object as a result of the accurate

perception of the object's situation or

predicament. Increases with familiarity/ similarity

of object and salience of display. 3. Theory of Mind

4. Cognitive empathy- Subject has represented

the state of the object as a result of the accurate

perception of the object's situation or

predicament, without necessary 'state matching'

beyond the level of representation. It can be

arrived at in a "top-down" fashion, involving

emotional circuits to a lesser extent. More likely

to be invoked for familiar/similar objects.

Synonyms: 5.True empathy, 6. Perspective-taking

Prosocial behaviors- Actions taken to reduce

the distress of an object.

Synonyms: Helping, succorance

1.Emotional contagion- Similar emotion is

aroused in the subject as a direct result of

perceiving the emotion of the object.

Synonyms: Vicarious emotion, emotional transfer

Sympathy- Subject feels "sorry for" the object

as a result of perceiving the distress of the

object. 2. Identification

Empathy- Subject has a similar emotional

state to an object as a result of the accurate

perception of the object's situation or

predicament. Increases with familiarity/ similarity

of object and salience of display. 3. Theory of Mind

4. Cognitive empathy- Subject has represented

the state of the object as a result of the accurate

perception of the object's situation or

predicament, without necessary 'state matching'

beyond the level of representation. It can be

arrived at in a "top-down" fashion, involving

emotional circuits to a lesser extent. More likely

to be invoked for familiar/similar objects.

Synonyms: 5.True empathy, 6. Perspective-taking

Prosocial behaviors- Actions taken to reduce

the distress of an object.

Synonyms: Helping, succorance

3 average female body mass/size, as

percentage of male

percentage of male

4 not including mandrills or macaques