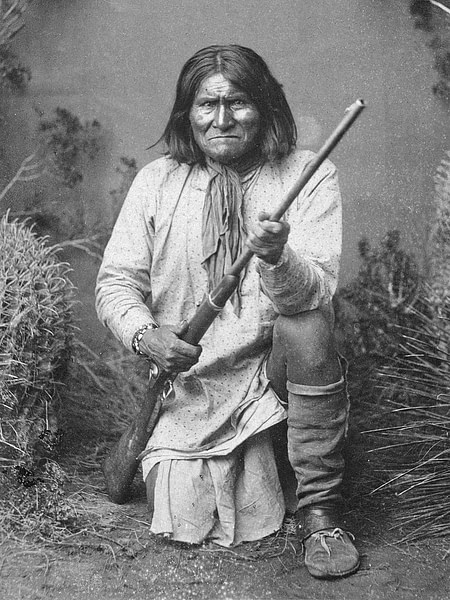

Geronimo (Goyahkla, l. c. 1829-1909) was a medicine man and war chief of the Bedonkohe tribe of the Chiricahua Apache nation, best known for his resistance against the encroachment of Mexican and Euro-American settlers and armed forces into Apache territory and as one of the last Native American leaders to surrender to the United States government.

During the Apache Wars (1849-1886), he allied with other leaders such as Cochise (l. c. 1805-1874) and Victorio (l. c. 1825-1880) in attacks on US forces after Apache lands became part of US territories following the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). Between c. 1850 and 1886, Geronimo led raids against villages, outposts, and cattle trains in northern Mexico and southwest US territories, often striking with relatively small bands of warriors against superior numbers and slipping away into the mountains and then back to his homelands in the region of modern-day Arizona and New Mexico.

He surrendered to US authorities three times, but when the terms of his surrender were not honored, he escaped the reservation and returned to launching raids on settlements. He was finally talked into surrendering for good by First Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood (l. 1853-1896), under the command of General Nelson A. Miles (l. 1839-1925), in 1886. None of the terms stipulated by Miles were honored, but by that time, Geronimo felt he was too old and too tired to continue running. Geronimo's surrender to Gatewood is told accurately, though with some poetic license, in the Hollywood movie Geronimo: An American Legend (1993).

Geronimo was imprisoned at Fort Pickens, Pensacola, Florida, before being moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Toward the end of his life, he became a sensation at the St. Louis World's Fair (1904) and President Theodore Roosevelt's Inaugural Parade (1905) as well as other events. Although one of the stipulations of his surrender was his return to his homelands in Arizona, he was held as a prisoner elsewhere for 23 years before dying in 1909 of pneumonia at Fort Sill.

Name & Youth

His Apache name was Goyahkla ("One Who Yawns"), and, according to some scholars, he acquired the name Geronimo during his campaigns against Mexican troops, who would appeal to Saint Jerome (San Jeronimo in Spanish) for assistance. This was possibly Saint Jerome Emiliani (l. 1486-1537), patron of orphans and abandoned children, not the better-known Saint Jerome of Stridon (l. c. 342-420), translator of the Bible into the Vulgate and patron of translators, scholars, and librarians.

Geronimo was born near Turkey Creek near the Gila River in the region now known as Arizona and New Mexico c. 1825. He was the fourth of eight children and had three brothers and four sisters. In his autobiography, Geronimo: The True Story of America's Most Ferocious Warrior (1906), dictated to S. M. Barrett, Geronimo described his youth:

When a child, my mother taught me the legends of our people; taught me of the sun and sky, the moon and stars, the clouds, and storms. She also taught me to kneel and pray to Usen [God] for strength, health, wisdom, and protection. We never prayed against any person, but if we had aught against any individual, we ourselves took vengeance. We were taught that Usen does not care for the petty quarrels of men. My father had often told me of the brave deeds of our warriors, of the pleasures of the chase, and the glories of the warpath. With my brothers and sisters, I played about my father's home. Sometimes we played at hide-and-seek among the rocks and pines; sometimes we loitered in the shade of the cottonwood trees…When we were old enough to be of real service, we went to the field with our parents; not to play, but to toil.

(12)

After his father died of illness, his mother did not remarry, and Geronimo took her under his care. In 1846, when he was around 17 years old, he was admitted to the Council of Warriors, which meant he could now join in war parties and also marry. He married Alope of the Nedni-Chiricahua tribe, and they would later have three children. Geronimo set up a home for his family near his mother's teepee, and as he says, "we followed the traditions of our fathers and were happy. Three children came to us – children that played, loitered, and worked as I had done" (Barrett, 25). This happy time in Geronimo's life would not last long, however.

Kas-Ki-Yeh/Janos Massacre & War with Mexicans

Although Geronimo gives the year as 1858 (Barrett, 29), most sources agree it was probably 1850/1851 when the Bedonkohe band camped outside the Mexican town known to the Apache as Kas-Ki-Yeh and to the Mexicans as Janos. While the Apache men were in Janos trading with the local merchants, a company of soldiers from Sonora attacked the camp, killing many, including Geronimo's mother, wife, and three children.

As all their weapons in the camp had been taken by the soldiers, the Bedonkohe survivors could not retaliate and returned to their homes. Geronimo related:

Within a few days, we arrived at our own settlement. There were the decorations that Alope had made – and there were the playthings of our little ones. I burned them all, even our teepee. I also burned my mother's teepee and destroyed all her property. I was never again contented in our quiet home…I had vowed vengeance upon the Mexican troopers who had wronged me and whenever I came near [my father's] grave or saw anything to remind me of former happy days, my heart would ache for revenge upon Mexico.

(Barrett, 30)

After this event, Geronimo declared war on Mexicans – not on the state of Mexico – but on any Mexicans – soldiers or civilians, men, women, and children – none would be spared. It was during his early attacks on Mexican outposts, it is said, that he heard the soldiers calling on San Jeronimo for help. This was interpreted by others as the soldiers shouting the name of their attacker, and the Apache war chief and medicine man Goyahkla became Geronimo.

Apache Wars & Geronimo Campaign

Geronimo was never a chief (though he is frequently referred to as one) but was, first, a "medicine man", commonly understood as a shaman, a holy man who received visions from the spirit world, interpreted dreams, and had been granted greater "medicine" (spiritual power) than others. He is said to have known of events occurring miles away, understood what an adversary was planning, and had visions of the future. Shortly after the deaths of his family, he became a war chief, a warrior who assumes command of a group of warriors before an armed conflict, but he was never a chief as defined as the overall leader of his people. Geronimo's chief was Mangas Coloradas ("Red Sleeves", l. c. 1793-1863), who, with his Council of Elders, approved of going to war. Geronimo was then made war chief of the group of warriors he led.

At first, his attacks were only focused on Mexican communities and garrisons, but after 1848, when Mexican lands officially became United States territories, he also raided Euro-American settlements, outposts, wagon trains, stagecoaches, and cattle trains. As with their Mexican adversaries, Geronimo's band spared no one in their raids on US citizens. In 1849, after Cochise declared war on the United States, Geronimo participated in joint attacks with his warriors and would continue to do so up through the 1860s.

Mangas Coloradas and Cochise had sworn to drive all White people from Apache territory but, by 1863, after Coloradas had been wounded again and was growing tired of war, he agreed to peace negotiations with US officials. Coloradas arrived at the camp of Brigadier General Joseph R. West under a flag of truce, but he was arrested. He escaped by cutting his way out of the tent but was taken again and executed. Cochise, Victorio, and Geronimo all swore revenge, and the Apache Wars continued with more casualties on both sides.

The US government was interested in the capture of all three, but, as Geronimo's name and reputation had become so notorious, focused their efforts on him through the Geronimo Campaign, which was a hopeless undertaking from the start because Geronimo would strike and then disband his warriors, later meeting at a secret rendezvous point, and also kept changing the locations of his camps. Native Americans, of whatever nation or tribe, who knew where he was would not tell, and even those who were not with him still would not betray him. After an attack on a train, and the execution of the prisoners, Geronimo related:

In a few days, troops were sent out to search for us but, as we were disbanded, it was, of course, impossible for them to locate any hostile camp. During the time they were searching for us, many of our warriors (who were thought by the soldiers to be peaceable Indians) talked to the officers and men, advising them where they might find the camp they sought, and while they searched, we watched them from our hiding places and laughed at their failures.

(Barrett, 71)

General George R. Crook (l. 1828-1890), tasked with capturing Geronimo, dispensed with the policy of sending only US troops after him and employed Apache and Navajo scouts. Crook was a veteran of the Great Sioux War (1876-1877) and had concluded, especially after his experience at the Battle of the Rosebud (June 1876), that Native people were better at fighting other Native people than anyone else. Crook sent two columns of US troops, led by Apache scouts, after Geronimo and the scouts were able to find his camps, destroying supplies, taking weapons, and killing anyone they found there. As this continued, Geronimo lost more and more of his warriors and, eventually, began to lose the support among his people who left his band and returned to the reservations.

Geronimo also began to lose support owing to his refusal to surrender, which many Apache began to feel was personal stubbornness and no longer in the best interests of the common good. Geronimo disagreed, citing the many instances in which the US government had made promises they had no intention of ever keeping – including the execution of Coloradas, who had arrived under a flag of truce for peace negotiations. Geronimo commented:

After all this trouble, the Indians agreed not to be friendly with the white men anymore. There was no general engagement, but a long struggle followed. Sometimes we attacked the white men – sometimes they attacked us. First, a few Indians would be killed and then a few soldiers. I think the killing was about equal on each side. The number killed in these troubles did not amount to much, but this treachery on the part of the soldiers had angered the Indians and revived memories of other wrongs, so that we never again trusted the United States troops.

(71)

Even so, as the Apache scouts continued to locate his camps, destroy his supplies and weapons, and kill those they found there, more of his supporters deserted him. Geronimo finally agreed to surrender to Crook but, after being warned that Crook would not honor the terms of the agreement, fled back across the border into Mexico and up into the mountains. Crook was then replaced by General Nelson A. Miles, who, through the efforts of First Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood, secured Geronimo's surrender in 1886.

Final Surrender & Imprisonment

The same Apache scouts that had helped bring Geronimo in, instead of being rewarded, were now disarmed, arrested, and sent with Geronimo and his band to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, and then on to Fort Pickens in Pensacola, Florida. Women and children were separated from the men and sent to Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida. All the scouts, some of whom held rank in the US army, were now considered hostiles who could not be trusted even though, without them, Geronimo would probably have eluded capture for many more years.

Fort Pickens was located off the coast of Pensacola on Santa Rosa Island, and local businessmen quickly exploited the presence of the "infamous Geronimo" and his Apache band as a tourist attraction. Flocks of tourists, sometimes as many as 400 a day, paid to take the boat out to the island and view the Apaches in their cells or the courtyard. Geronimo, and others in his band, made the most of this by requesting gifts from tourists and charging for photographs. Even so, most of the time, the Apache prisoners were forced to perform hard labor. Geronimo commented:

Here [at Fort Pickens] they put me to sawing up large logs. There were several other Apache warriors with me and all of us had to work every day. For nearly two years we were kept at hard labor in this place, and we did not see our families until May 1887. This treatment was in direct violation of our treaty [of surrender].

(Barrett, 101)

News that Geronimo and his men had been separated from their families led to public pressure to reunite them in 1887. Women and some children were then relocated from Fort Marion to Fort Pickens, but many of the children had already been taken by US authorities and sent to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, for indoctrination and assimilation. In 1888, as yellow fever threatened Fort Pickens, the Apache were moved to Mount Vernon Barracks in Mobile, Alabama, where many died of tuberculosis.

The survivors were then relocated to Fort Sill, Oklahoma despite the terms of Geronimo's surrender, which had stipulated he would be able to return to his homelands in Arizona. According to US military authorities, this was impossible because Arizona's civil authorities wanted him hanged for murder. When the Fort Apache Indian Reservation was established in Arizona in 1891, however – where Geronimo could have lived beyond the reach of these authorities – he continued to be held at Fort Sill. He would remain a prisoner of the US government for 23 years, and he never saw his homeland again.

Conclusion

Geronimo was allowed out of Fort Sill, under guard, to attend various events as a tourist attraction. He traveled to New York for the Pan-American Exposition in 1901 and the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904. That same year, he signed on as a feature in Pawnee Bill's Wild West Shows, and here, as at Fort Pickens, Geronimo made the most of the situation by selling tourists buttons off his coat; he would then buy more buttons, sew them on, and again sell "official buttons" from the coat of "Indian Chief Geronimo."

In 1905, he participated in the Inaugural Parade of President Theodore Roosevelt and, that same year, granted an interview to S. M. Barrett, which was published as his autobiography in 1906. He spent much of his later life either tending a small plot of land at Fort Sill or traveling under armed guard to these various events. In February 1909, he was riding home after a night of drinking when he fell from or was thrown by his horse and spent the night passed out on the cold ground. He died on 17 February 1909 of pneumonia, and, allegedly, his last words were regret at having ever surrendered to US authorities.