Auschwitz was a concentration and extermination camp in German-occupied Poland operated by the Nazi SS from 1940 to 1945. Around 1.1 million people died at the Auschwitz complex from overwork, malnutrition, disease, and in the gas chambers. Jewish people made up the vast majority of those who were killed.

The Auschwitz I camp was the administration centre of the complex. The camp at Birkenau (Auschwitz II) included gas chambers where those the Nazis had identified as enemies were murdered, principally Jewish people from across occupied Europe as part of the Nazis' 'Final Solution'. Other victims included Polish political prisoners, Soviet prisoners of war, Romani people, convicted criminals, and many others. Monowitz (Auschwitz III) provided forced labourers for the construction of nearby German-owned factories. Today, Auschwitz is a museum and memorial to those who suffered and died there.

Enemies of the State

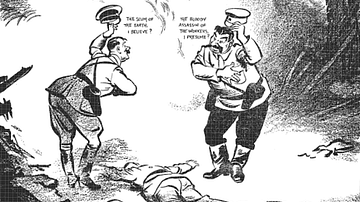

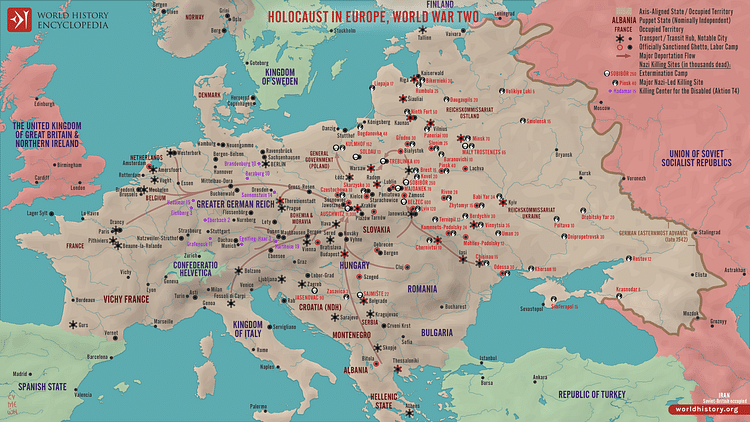

The leader of Nazi Germany Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) had long declared that Jewish people were enemies of the state and responsible for Germany not fulfilling its full economic and cultural potential. The 1935 Nuremberg Laws stated that having three or four Jewish grandparents made one a Jew for the purposes of the Nazi regime. First, Jews were encouraged to emigrate, and those who remained faced daily discrimination and violence from the Nazi paramilitary groups the SA (Sturmabteilungen) and SS (Schutzstaffeln). Following the pogrom against Jews known as Kristallnacht in November 1938, Jews were deprived of certain rights such as the right to own a business. Similar measures were applied to Jews in Nazi-occupied territories once the Second World War (1939-45) began. From 1942, Jews were confined to specific areas, ghettos of larger towns and cities. Then came the 'Final Solution' to what Hitler called the 'Jewish Problem', that is to work Jews to death in labour camps or send them directly to extermination camps, of which Auschwitz became one of the most notorious. It was not only Jews who were sent here but also other 'enemies' of the state such as political opponents to the Nazis, Communists, Jehovah's Witnesses, Freemasons, and those people with physical disabilities, amongst many others.

The Auschwitz Complex

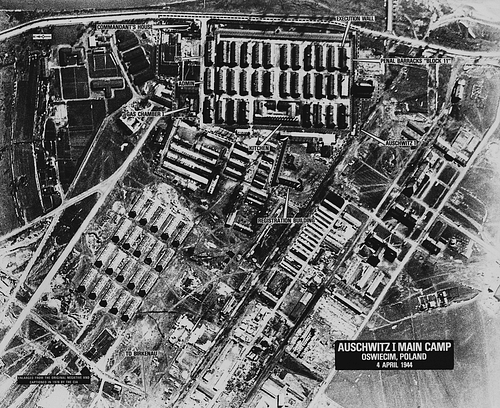

The Nazis located what would become their death camps in locations remote from the German people, and so occupied Poland was selected as one of the best places to build them. The original Polish name for Auschwitz was Oświęcim. The Auschwitz complex, a former artillery and cavalry barracks around 53 kilometres (33 miles) west of Kraków, ultimately grew to consist of three concentration camps and 50 subcamps. The first camp, Auschwitz I, initially operated from June 1940 as a concentration camp for Polish political prisoners, of which there were thousands following the invasion of Poland in 1939. This camp ultimately had 28 barracks capable of holding 17,000 people. There was a punishment block where prisoners were kept in solitary confinement, made to stand for days, or kept in its cellars and denied food and water; there was also torture, such as being hung from the ceiling with one's arms behind one's back. Auschwitz I was also the administrative centre of the entire complex.

Auschwitz II, also known as Birkenau, ultimately became the part of the complex where people were murdered in gas chambers. In operation from March 1942, Birkenau was located about 2.5 kilometres (1.5 miles) from the much smaller Auschwitz I. Birkenau had around 300 wooden barracks and 50 brick barracks and could hold around 100,000 prisoners. Birkenau's four complexes of gas chambers could each murder 2,000 people at one time, and they were operated around the clock. There were large ovens and a crematorium for processing the corpses (which were also burnt in open pits).

Jews arrived by train from across German-occupied Europe, first from Slovakia and then from across occupied Europe. In 1944, over 400,000 Jews came from Hungary alone. Jews from Poland itself were sent to Auschwitz, too.

Auschwitz III, located near Monowitz, about 6 kilometres (3.7 miles) from Auschwitz I, became the third major camp. This camp was in operation from October 1942. Besides the standard Nazi concentration camp facilities, there were, too (in Auschwitz II), "family camps" where prisoners lived as families and could wear civilian clothes. One such camp was for propaganda purposes and the second was used to detain Romani and Sinti people.

Death Now or Death Later

The prisoners mostly arrived at Auschwitz by train, typically with around 1,000 people (although sometimes much more) in each train which was made up of wagons designed to transport goods or livestock, not people. The train journey could take several hours or several days as they came from across occupied Europe. The conditions were horrific with very little space to breathe or water to drink. It is estimated that a significant number of the prisoners died before they reached the camp. Prisoners often arrived at night so that the bright floodlights dazzled them and made resistance less likely.

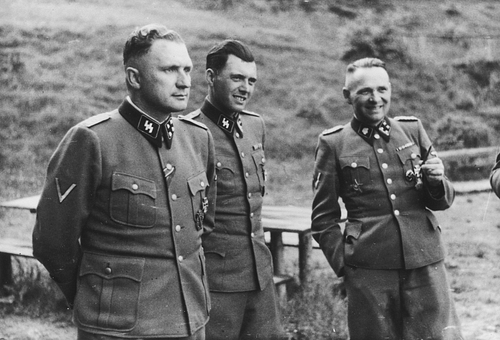

The new Jewish arrivals were immediately sorted into life or death groups, as here explained by the camp's first commandant Rudolf Höss (1901-1947):

We had two SS doctors on duty at Auschwitz to examine the incoming transports of prisoners. These would be marched by one of the doctors, who would make spot decisions as they walked by. Those who were fit to work were sent into the camp. Others were sent immediately to the extermination camps. Children of tender years were invariably exterminated since by reason of their youth they were unable to work…at Auschwitz we endeavoured to fool the victims into thinking that they were going through a delousing process…Of course frequently they realised our true intentions and we sometimes had riots and difficulties. Very frequently women would hide their children under clothes but of course when we found them we would send them to be exterminated. We were required to carry out these exterminations in secrecy, but of course the foul and nauseating stench from the continuous burning of bodies permeated the entire area and all of the people living in the surrounding communities knew that exterminations were going on at Auschwitz.

(Neville, 49)

One of the doctors referred to by Höss as selecting new arrivals was Josef Mengele (1911-1979). Wearing a white coat and sometimes matching gloves, Mengele decided who went to the gas chambers and would be detained in the concentration camp. Mengele also pulled out people he wanted for his own horrific pseudo-scientific experiments. Even for those destined for use as forced labour, the first stages of processing revealed what was to come. Dr Lucie Adelsberger, a prisoner of Auschwitz, describes the processing of new arrivals destined for the labour camps:

We undressed, had our hair cut – no actually our heads were shaved to stubble; then came the showers and finally the tattoos. This was where they confiscated the very last vestiges of our belongings; nothing remained…no written document that could have identified us, no picture, no written message from a loved one. Our past was cut off, erased…We were put in prison garb, with no underwear, only a thin chemise…We were given wooden shoes with shreds of Jewish prayer shawls as foot wrappings. Then we got our numbers burned into our left forearm and sewn onto our clothes with a triangular badge that identified each prisoner by color. We were cut off from the whole world out there, uprooted from our homeland, torn from our families, a mere number, of significance only for bookeepers.

(Cesarini, 656)

At Auschwitz, those Jews selected for labour were separated into male and female groups. If a labourer became too weak or too ill to work, then they were sent to the gas chambers. Labourers were involved in any project the SS thought useful or constructed factories or did factory work since many German firms had relocated to occupied Poland to escape the Allied bombing of Germany. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial, the Auschwitz III camp "was established in Monowice to provide forced laborers for nearby factories, including the I.G. Farben works."

The life expectancy of an Auschwitz labourer could have been as low as six months, although life expectancy varied greatly. In just one example, a transport train carrying 1,000 people arrived at Auschwitz on 24 August 1942. Most of the women, the men over 45, and all 544 children were sent immediately to the gas chambers. Just 90 men and 11 women were selected from the arrivals to work as labourers, of these, only seven of the men and none of the women survived their experience at Auschwitz.

Camp Conditions

In the camps, food rations were not sufficient for prolonged survival. Prisoners slept on hard bunks, often mere holes in a brick wall where four prisoners shared a compartment. In the early years there were no toilets in some of the huts, these were in a separate block and access was limited by the guards. The inmates became infested with lice and fleas and rats gnawed at those too weak to shoo them away. Clothing was scant, even in winter, and many labourers were not given shoes. In the worst periods, hundreds died every day in Auschwitz from malnutrition, overwork, and disease (there was at least one typhus epidemic). Beatings took their toll, too, as did the roll calls where each prisoner had to stand – sometimes for hours – each morning and at the end of each day in all weather conditions.

Seweryna Smaglewska, a prisoner in the Birkenau women's camp, describes the living conditions there:

There were no roads, no paths between the blocks. In the depths of these dark dens, in bunks like multi-storied cages, the feeble light of a candle burning here or there flickered over naked, emaciated figures curled up, blue from the cold, bent over a pile of filthy rags, holding their shaved heads in their hands, picking out an insect with their scraggly fingers and smashing it on the edge of the bunk – that is what the barracks looked like in 1942.

(Cesarini, 528)

There arose a small hierarchy within the prison community. Some people tried to bribe favours from the guards or report fellow prisoners and so gain some material advantage for themselves, such as better rations. One might become a prisoner trustee or work unit supervisor (kapo), but this involved an expectation to beat fellow prisoners. Some prisoners were selected to work as clerks, as assistants to the doctors and their experiments, or they were set tasks such as disinfecting and tattooing other prisoners. In the end, though, all prisoners were destined for the same final destination.

The Gas Chambers

Auschwitz II's gas chambers were operational from March 1942. There were ultimately six gas chambers. As Höss noted, some attempt was made to convince the prisoners sent into the gas chambers that they were merely going to be showered. The illusion was encouraged by signs on the chambers reading 'Baths' or 'Showers' and there were pleasant lawns and flower beds around the chambers. Coming from habitation where water was severely restricted or even cut off for days at a time, the idea of a shower must have had some appeal. For the labourers deemed too unfit to carry on working, they knew only too well the purpose of the chambers they were forced to enter.

Granules of a powerful pesticide called Zyklon B produced a lethal gas (hydrogen cyanide) when mixed with air, and this gas was used to kill those inside the chambers. It took between 10 and 15 minutes to kill. The guards knew when it was over because the screaming had stopped. Dealing with the dead was a duty of special prisoner detachments known as Sonderkommandos. As part of the dehumanisation of the victims, a measure was introduced which forbade the Sonderkommando workers from using words like 'body' and 'corpse', instead they had to use terms like 'figures' or 'rags'. Hair and any gold or other meal teeth were removed from the corpses. Human hair was sold to factories that produced felt. The gold would be ultimately melted down along with other confiscations from prisoners like gold-framed spectacles, rings, earrings, and pocket watches. The gold ingots were then deposited in the SS's secret account in the Reichsbank. The bodies were taken to the crematorium section of the camp where they were burned in brick ovens. The bones were then ground in mills, and "the ashes were used as fertilizer in the nearby fields, dumped in local forests, or tossed into the river, nearby" (Friedländer, 503).

Performing the more gruesome work in the camp earned those prisoners better rations, but the respite was brief since prisoners who dealt with the dead often died in their work or they could be sent to the gas chambers themselves to ensure there were no witnesses to reveal to outsiders Auschwitz's horrors. "By 1944, according to some sources over 6,000 a day were murdered, and 250,000 Jews from Hungary were exterminated in six weeks" (Deer, 60). The Auschwitz Memorial Museum puts this figure higher at 330,000. So many were killed, the crematoria could not keep pace with the gas chambers, and so many bodies were burned in open pits.

A Measure of Justice

There was an underground resistance movement of sorts at Auschwitz. Prisoners helped other prisoners attempt to escape. In October 1944, some prisoners even managed to damage one of the gas chambers, but the reprisals from the SS were brutal. Around 80 or so prisoners who escaped during the confusion of this incident were captured and executed. Another 200 prisoners believed to have been involved in the sabotage were also executed.

The Allies were not certain of what was going on in camps like Auschwitz. A handful of prisoners did escape from Auschwitz over the years, but their accounts seemed too fantastic to be true. When the real purpose of Auschwitz had finally been established, the Allies discussed what could be done. The answer was very little. Some leaders were in favour of bombing the complex, but this, of course, would have led to thousands of prisoners being killed.

With the war going badly for Germany, the operation of Auschwitz's gas chambers was closed down on the orders of the leader of the SS Heinrich Himmler (1900-1945) in November 1944. The camp was finally liberated – there were still at least 7,000 prisoners there – by the advancing Red Army of the USSR on 27 January 1945. The SS had by that time already begun to destroy what they could of the camps' mechanisms of death in order to hide their true function. The SS had also moved by train or forced-marched tens of thousands of Auschwitz prisoners back to Germany. Nevertheless, survivor testimonies were systematically collected together, and the true horrors of Auschwitz were revealed. Time continued to add to the body of eyewitness accounts. For example, in 1980, several children were digging in the area and came across a buried thermos flask, inside was a manuscript written in Greek by an Auschwitz prisoner who described what had happened there.

In the post-war Nuremberg trials (1945-6), Ernst Kaltenbrunner (1903-1946), Chief of the Reich Main Security Office, which was responsible for the overall administration of camps like Auschwitz, was found guilty of crimes against humanity and hanged in October 1946. Höss was hanged at the camp he had commanded by the Polish authorities in April 1947. The Doctor Trials (1946-7) brought to justice 23 doctors, several of whom had conducted experiments on prisoners in the camps. 16 doctors were found guilty of crimes against humanity, and seven received the death sentence. Mengele escaped Allied detection, and he eventually escaped to South America. Adolf Eichmann (1906-1962), who was responsible for the transportation of prisoners to the camps, also escaped detection but was ultimately brought to trial in Israel, found guilty of crimes against humanity, and hanged in 1962.

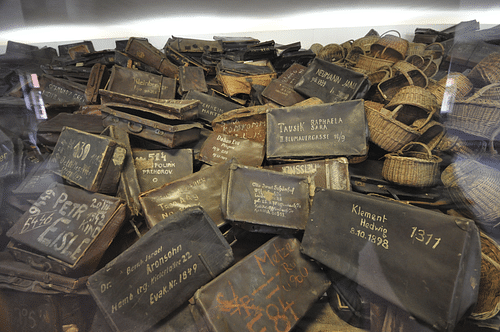

The USSR's initial assessment of how many people had died at Auschwitz was put at 4 million people, but this is considered an exaggeration by most historians. Today, Auschwitz is a museum site, and the official number of victims is there stated as 1.1 million people. This figure includes around 19,000 Romani people and at least 800,000 Jewish people, although some Holocaust historians put the figure higher, such as David Cesarini, who prefers 900,000 (Cesarini, 747), while the Auschwitz Memorial puts the figure at one million. The precise number of those who suffered at Auschwitz is difficult to determine because of the scale of the operation and the SS's deliberate intention to hide that scale. In any case, such numbers are difficult to comprehend. The Auschwitz museum combats this difficulty by showing rooms full of the personal belongings of the victims. The enormous piles of such mundane items as luggage and spectacles bear silent but powerful witness to the scale of the tragedy that went on here.

With gratitude to the Auschwitz Memorial for its assistance in the publication of this article.